The plasticity of clay is key to its natural volubility: its inherent potential to speak materially and so to articulate narrative in the most elemental sense. An accommodating substance, clay moves easily under the energy of a compressive force, whether a disinterested force like gravity or one as motivated as the pressure of an artist’s fingertips as they strive to impart meaning to the world. The ability of clay to hold the shapes that it acquires under the influence of such forces makes it a faithful chronicler of events in a story of creation: a record of the physical genesis of form. Material narrative comes to clay so readily that some who work intimately with the medium feel obliged to allow it a significant degree of self-determination after imposing upon it only the rudiments of form. (Such restraint on the part of the maker in deference to the inherent narrative inclinations of clay is typical of some phases of the Japanese ceramic tradition, for example.) Other makers take the opposite tack, treating clay as a malleable tabula rasa on which to inscribe the full content of their intentionality. Clay has no preference between these polarities; it is amenable to any position on a spectrum from assertive presence to obedient vehicle, from material narrative to content narrative.

In the service of art, clay typically carries multiple, simultaneous narratives that relate to one another in ways calculated to compound meaning. Stories of transition between material states are unmotivated, fortuitous, arising from the natural tendency of clay to respond to the forces that act upon it, but they can be anticipated and even encouraged by the artist for aesthetic or discursive purposes. The result of such encouragement often appears more like a negotiation between clay and maker than an imperious forcing of the artist’s will upon a submissive medium.

Gravity and shrinkage – the latter of which can leave fine networks of fissures in the surface of clay while in the drying stage or even tear gapping wounds in that surface if the drying process is rushed – are two frequent instigators of unmotivated material narratives in ceramics. Their traces relate stories of creation that assert the independence of clay from absolute human control. More common as factors in this mode of material narrative are the consequences of kiln atmospheres, particularly those generated by wood-fired kilns. Flashing – a range of visual surface effects that arise chiefly from differences in oxygen levels as raw clay is transformed into ceramic through heat – and natural glazing, as wood ash settles on clay surfaces and vitrifies, were historically the most common atmospheric influences on material narrative. That these are not represented among the works of the exhibition can in part be attributed to the prevalence of gas and electric kilns today, but, more important, it may also signal a desire among many of the artists to move symbolically as well as literally beyond the vessel, to distance their work from the associations of clay with craft and its historical technologies, particularly the making of functional pottery in wood-fired kilns.

It should be noted that one of the most significant sources of material narrative in both historical and contemporary ceramics does not involve clay at all, except as a kind of stage for the actions of another material altogether. Glaze, a vitreous substance, has been employed since antiquity, to seal the porous walls of earthenware vessels and to enhance the aesthetic appeal of objects produced in all clay bodies. Glazes, particularly lead-based glazes, tend to flow as they melt during firing, creating visual effects more liquid than solid, more active than static. In the finished object, each gleaming rivulet of glaze is a record of a descending migration and each glistening drip marks the point at which molten glass cooled and thickened sufficiently to finally defy gravity. It is no coincidence that medieval Japanese connoisseurs of glaze often found in its effects intimations of the changing seasons. Glaze trails not only embody the physical traces of movement across space; they also materially record time.

Both the metaphorical possibilities and the more directly iconic potential of running glaze are exploited in Thomas Schütte’s Eierköpfe. The aqueous effects of glaze, its translucence and fluidity, readily conjure the albumen and yolk of a cracked egg and the bodily fluids – blood, mucous, and tears – of a human head. Rhetorically these liquids evoke the frailty and ephemerality of life, linking the Eierköpfe to a number of other melancholy narratives in the exhibition involving memento mori. Schütte’s eggheads are manifestly subject to external factors, the force of gravity and the weight of mortality. Though isolated ovoids bearing only the most rudimentary references to facial features, his Eierköpfe are quite different in effect from the similar form in Constantine Brancusi’s famous Sleeping Muse of 1910. The polished bronze of the latter, a material closely associated with the transcendent universals of classicism, makes it an inviolate monument to the persistence of ideal form across eternity. In contrast, Schütte’s Eierköpfe, in their slumping of clay and dripping of glaze, are more closely evocative of organic form, with its bonds to the cycle of life and its inevitable surrender to entropy.

In its raw state, clay serves naturally as a metaphor of the organic, evolving from molecules formed in a watery environment and remaining malleable only so long as that vital relationship with water is maintained. Raw clay and the human body are alike in this respect, with the former typically containing about 30% water and the latter roughly 50%. Despite this kinship, human interaction with clay has almost always resulted in a kind of death of the material. The drying and firing process through which water is removed and clay is ultimately converted to ceramic eliminates the potential for growth that an additive medium naturally embodies, rendering a plastic material effectively inert. Ceramic objects can, of course, acquire a different kind of metaphorical life through utility, passing through time and space and interacting with their environment in ways that both respond to and transform it, but that is life largely in its experiential sense rather than its biological essence. Ceramics as a field has for the most part contented itself with metaphors of this relational sort, but artists not bound to the traditions of a discipline in which function has been an influential, even governing, concept for millennia have felt freer to explore the aesthetic and symbolic possibilities of raw clay. In the early 1970s, for example, California artist Jim Melchert performed his famous Changes, in which he dipped his head in clay slip and allowed it to dry into a crusty second skin, and in the 1990s New York artist Walter McConnell began a series of large, plastic-sheeted terrariums in which mounds of raw clay sculpted into landscapes established temporary biospheres through evaporation, condensation, and precipitation.

Phoebe Cummings, The Fall, 2019

To use clay in this way is to do more than evade the term ceramic. It is to revise one of the oldest aphorisms in a long history of Western reflection on the nature of art: ars longa becomes ars brevis. As it dries, raw clay hardens and eventually sloughs away as dust, evoking the ephemerality of life in the singular: the life of an individual organism, whether a hyacinth or a human being. Raw clay from this perspective equates art and artist mortally rather than projecting the former into an infinite future as an undying surrogate of the latter. When Phoebe Cummings creates a narrative of nature in a raw-clay, site-specific installation she is aware from the outset that none of her efforts, not the mental exertion of envisioning a composition nor the physical labor of shaping the formless medium of clay into the mediated form of sculpture, will result in an enduring masterpiece, or even an artwork at all in the conventional sense. Raw clay differs temperamentally from stone, bronze, or steel. It is restless, constantly changing. Like the artist’s own life, each of Cummings’s installations has a beginning and an end, but in between there is no point of completion. Between the initial masses of raw clay and the terminal masses into which the installation must inevitably be dismantled, there is no stage at which one can say that a work is fully present, fully independent of a process of transformation. The artist ends her engagement of the material once her concept has been realized, but the material continues to transform, slowly desiccating until the day when it must be broken up and removed. Then, all that remains is an absence hinted at in memories and photographs. If there is melancholy in this mortality, there is also a message. Life in the singular is finite, and raw clay can reference this, but raw clay can also evoke life in the collective: the vitality that, like the nature that Cummings represents, transcends any single organism and endures beyond the unending stream of deaths. Raw clay may dry, shrink, and disintegrate into dust, but its remains can be recycled, reconstituted by the vital element of water, and returned to plasticity and the potential for creation.

This is, of course, not the case for clay as ceramic. Clay that has passed through the firing process has been deliberately removed from a cycle of change, has been chemically transformed through the burning off of carbon and sulfur, a breaking of bonds with molecular water, inversion of the crystalline structure of quartz, sintering of clay particles together, and, finally, vitrification of those elements capable of melting. Ceramic, particularly high-fired stoneware and porcelain, is more akin to marble – a metamorphic rock formed from sediment under intense heat and pressure – than anything organic. It is no accident that potsherds are the staples of archaeology; they endure across the ages, preserving their traces of human ingenuity and industry as persistently as documents in stone. Nevertheless, pottery, because it has infiltrated so many aspects of sociality, has acquired rhetorical associations with life. The most mundane evidence of this is reflected in the figurative terminology for the parts of a vessel – from foot to belly, shoulder, neck and mouth; less obvious, but more consequential, are the many ways in which humans have tended to reflect on the life of utilitarian ceramic objects in domestic service, to link them to rituals and rites of passage, and even to treat them as metonyms for those who possessed them in life.

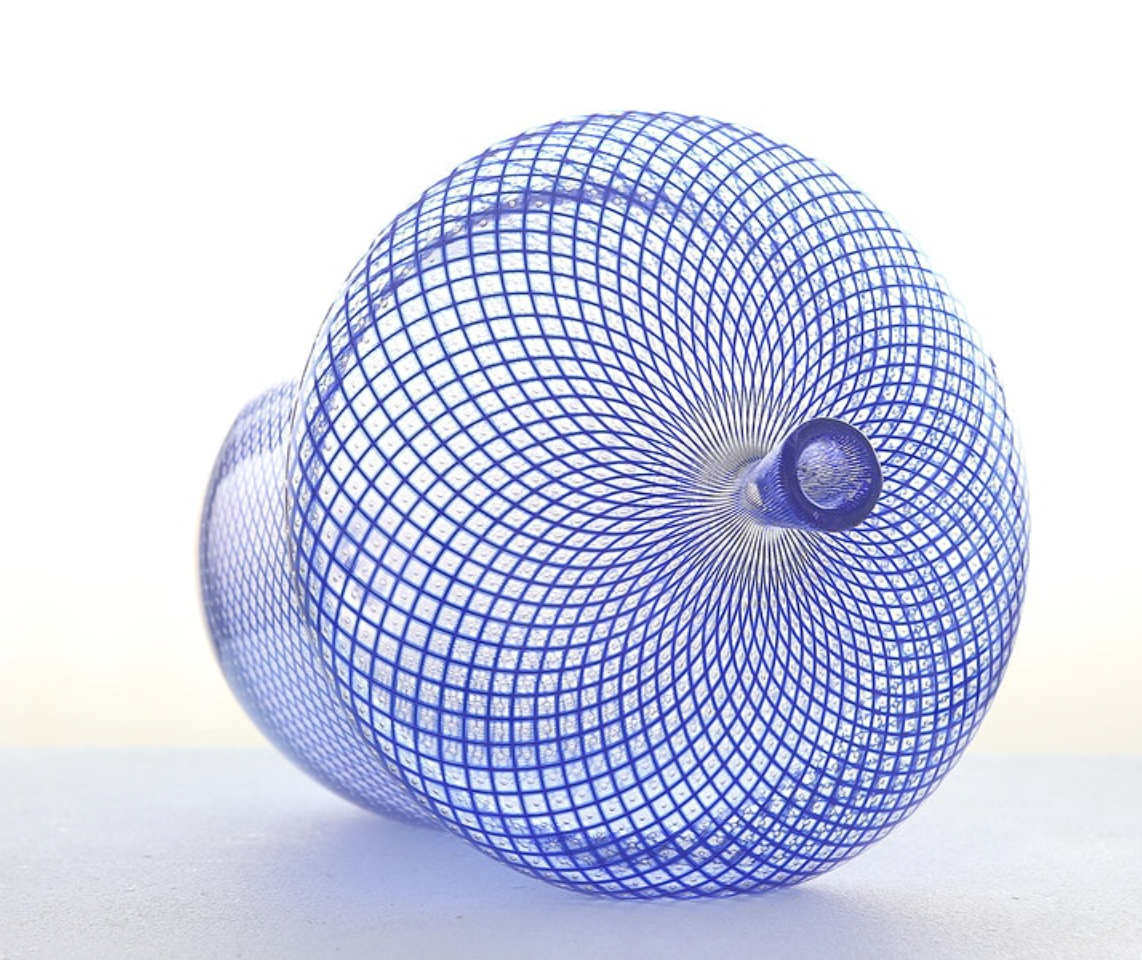

Bouke de Vries ‘Cloud 2’

That which can live must inevitably die, and this accounts in part for the power of expression in Bouke de Vries’ Cloud 2, a towering icon of an atomic blast articulated through a detritus of defunct and dismembered ceramic vessels and figurines. Ceramic is a frangible material, prone to shattering when under tension. When a ceramic object breaks, each sherd rings forever with the traces of destruction. The sherds themselves recall a once-whole form that no longer exists, and in this respect conjure material narratives of violence and death. Cloud 2 employs this association in synergy with the representation of an atomic mushroom cloud to decry the use of high technology for the most terrifying of human intents: the mass destruction of human beings themselves. At the same time, De Vries’ work is curiously complex, embodying antitheses in a metaphor of the cycle of life rather than simply emblematizing death. If the shattered plates and figurines embody destruction, the process of composing them into a new and meaningful configuration is surely one of resurrection, as if the artist looked upon the fragments of ceramic ruin and posed the prophetic question, “Can these bones live?” De Vries, in fact, has made a career of sculpting through resurrection, of salvaging sherds and giving them new life in reconfiguration, sometimes by connecting them with Perspex rods and sometimes through the Japanese technique of kintsugi, in which the sherds of a broken vessel are reconnected with a mix of lacquer and gold dust that not only restores the vessel to wholeness but imparts to it a beauty of experience that exceeds that of any material perfection.

The slumping of wet clay in response to the influence of gravity, the trails left by a glaze as it flowed in molten liquidity over surfaces during the transformation of clay into ceramic, the shrinking and cracking of raw clay as it surrendered its moisture to the surrounding air, the sharp edges of a sherd once part of a larger, now dismembered, form – these are all factors in material narratives that could be called disinterested, unmotivated by anything but natural forces acting on material objects. Such naturally occurring narratives can be exploited to complement narratives of other sorts, but material narratives in clay can also be of a more obviously motivated character. The distinguishing factor is consciousness: the impact of human intention on the physical form of clay. The simplest of such motivated material narratives arise from the process of modeling by hand: an immediate transferal of energy from the artist’s body to the clay body and a subsequent modification of the mass and surface of the medium at the artist’s will. These kinds of narratives may be nothing more than an articulation of two discernable states or events and a moment, however brief, that links them in sequence: the maker’s finger rested here, and then it was dragged across the surface to there, leaving a faint rill in the wet clay. Such overt material narratives of the process of making are primordial; they have a history that dates back roughly 30,000 years, when Neolithic fingers pinched clay near the fire pits of Dolni Vestonice in Central Europe. At the same time, much of the history of ceramics has been given to reducing or even eliminating altogether these kinds of physical traces and the narratives of making that they convey. The cool perfection of Ching Dynasty imperial bowls, for example, seems to transcend the world in which human hands exert any influence over form, and the uniformity of product sought during the European Industrial Revolution gave rise to ceramic wares more evocative of machine technologies than the hand-working techniques of generations of previous potters.

Material narrative in clay never fully disappeared, despite the perfection of technologies for eliminating it, and in the second half of the twentieth century, it resurged as a deliberately cultivated trait diagnostic of modern ceramic art. It is no accident that this occurred at a time when material narratives in paint provided a sense of radical novelty for Abstract Expressionism. The drips in a Jackson Pollock painting, for example, each materially reflect movement of the artist’s body through space, and, in turn, adumbrate an internal struggle in which the artist’s very identity hung in the balance. In the field of ceramics, the work of Peter Voulkos, the central protagonist in what has been called the California Revolution in Clay, helped to popularize motivated material narrative by introducing to clay the equivalent of Abstract Expressionist painting. Groping, slashing, and pummeling clay and leaving the evidence of this manipulation obtrusive in the finished form, Voulkos created massive platters and “stacks” that subverted the functional nature of the vessel – for all practical purposes rendering it sculptural – and asserted that clay was a natural medium for both material narrative and, through its connotative potential, expressive narrative.

Jørgen Haugen Sørenson

The close relationship between these modes of narrative, the material and the expressive, is epitomised in Beyond the Vessel by the modeled sculptures of Jørgen Haugen Sørensen, which employ the idiom of fingers on a malleable surface to convey the testimony of a witness to the horrifying depths to which human nature can descend. Sørensen’s closest precursor in terms of his material narratives is not Voulkos, a paragon in the ceramic tradition, but rather the sculptor Rodin, whose roughly modeled maquettes in clay are some of the most materially expressive representations ever to have been fashioned in art. Sørensen’s Justizia IV reimagines the torment of Rodin’s Thinker, situating a despondent figure on a plinth from which to contemplate not a multitude of damned souls in the abyss of hell but rather a rising mountain of death manifesting a hell on earth. The rough marks of the artist’s interaction with clay relate more than a story of physical creation: they convey a powerful impression of violence, a scraping and tearing of the clay body, that reflects the presumed actions behind the mound of cadavers, but also, and more important, embodying the turmoil of Sørensen’s emotions while reflecting on the pervasiveness of brutality in the contemporary world. The deeply personal nature of the expression is confirmed, ironically, by the layer of glaze applied to the work as a kind of damper on the subjective. Wishing to create monuments testifying to the injustice still rampant in the contemporary world Sørensen enveloped his sculpture in a monochrome white with the intention of neutralizing some of the visceral material effects and elevating the narrative from the personal level to that of the universal.

Intimacy with clay through the direct actions of the fingers, or simple tools that serve as prostheses of these and largely preserve the immediacy of touch, is the primary avenue by which motivated material narrative is generated in clay, but other strategies are at the artist’s disposal as well. Christie Brown demonstrates that intentional storytelling in material terms is possible when using some of the very tools through which material narrative can be effectively reduced or even eliminated in the working of clay. Brown’s sculptures are often assembled from combinations of handwork and mould-made forms. In general, moulds promote multiplicity rather than singularity; slipcast forms, for example, can be virtually indistinguishable from one another. Brown, however, utilises press moulds, or casting moulds, and takes particular interest in the physical deviations that can occur between multiples produced through this hands-on technology. Distended features, wrinkles, or cracks can arise and contribute materially to the formation of narratives when clay is removed from a press mould or when a moulded form is integrated into a larger composition. Like the traces of the incommensurable that some Surrealists found in simple details of surfaces – the veins of a leaf, or the raised grain of a wooden floor after countless scrubbings – material idiosyncrasies can be revelatory for Brown, whose most recent works reflect on the psychological implications of animal and human hybridity reflected in the persistence of ancient European folk rites in which participants still don animal attributes in ritualistic regression to an intuitive, instinctive relationship with the world.

Under the influence of artists such as Voulkos, motivated material narrative gained immense popularity as a sign of modernist expression in the artistic working of clay in the third quarter of the twentieth century, but the logic of the avant-garde dictated that eventually this quality should itself be negated through subsequent revolution. Such negation occurred as early as the Seventies in the experiments of Richard Shaw with slipcasting, a technique selected deliberately to agitate the emotions of hands-on expressionist potters and sculptors. Shaw, and other artists such as Marilyn Levine, went on to perfect a genre of trompe l’oeil ceramics that shifted the emphasis from the material narratives of real objects fashioned from clay to the simulated material narratives of feigned objects merely represented by the works. Levine, for example, employed the natural fissuring of drying clay to convey the effect of cracking leather in her famous illusionistic renditions of handbags and briefcases, in effect directing the viewer to disregard actual material and the stories it bore of its own physical creation and focus instead on the simulation of such narratives. In this respect, material narrative became subtly fused with content narrative.

Bertozzi & Casoni ‘Autonno’

The Archimboldo-inspired allegorical heads of seasons created by Bertozzi & Casoni are tours de force of an ability to divert the viewer’s attention from the actual materiality of ceramic and glaze to the illusion of material in a cornucopia-like abundance of ersatz fruits, vegetables, grains, and flowers (and even the accumulation of litter that places Summer squarely in the context of environmental calamities that confront us today). Here clay might begin to seem incidental, though certainly it is essential to the surprise aspect of trompe l’oeil art. These sculptures would, after all, provoke a significantly different response were they composed of organic objects rather than fired clay, since the ability to instigate moments of epiphany would be lost. Bertozzi & Casoni achieve the power of illusion, like all conjurers, not by true miracles of transformation but rather through diversion of the viewer’s attention from the actual state of affairs, in this case the real materials comprising the allegorical heads. If this visual sleight of hand constitutes a significant evasion of the kinds of material narratives toward which clay is naturally inclined, it does not signify rejection of the ceramic tradition. On the contrary, Bertozzi & Casoni seem to pay conscious homage to the trompe l’oeil ceramics of the famous sixteenth-century French craftsman Bernard Palissy, whose distinctive “rusticware” simulated organic reality not only through its moulded-from-life components of fish, snails, eels, frogs, snakes, and the like but also through its skillful employment of enamels to complete the picture of unadulterated nature. Bertozzi & Casoni may elaborate their narratives almost exclusively through content, but their works suggest a profound awareness of the history of ceramics as well as the general history of art.

Such awareness is reflected in the work of many ceramic artists today, just as many artists who work in clay maintain a deep appreciation for the narrative potential of the material. At the same time, contemporary ceramic art – whether in general or in the narrower sense of a discipline defined by a specific discourse and set of practices – often tendentiously separates itself from the history of ceramics and patently negates the material narrative natural to clay. The haunting Moss People of Kim Simonsson, for example, may be fashioned from stoneware, but the distinctive surfaces that link their materiality to their content – achieved through an accumulation of paint and nylon fiber – owe nothing to the material nature of clay. In fact, they camouflage it. That such substances as flocking, tool dip, fabric, and even sequins are regularly employed to cover every centimeter of surface in some contemporary ceramic sculptures only underscores the diversity of ways in which clay can be employed as a medium in art. In fact, with little difficulty one could construct a spectrum of contemporary works ranging from those in which clay as a material is eloquent and granted almost complete control over the narratives that it conveys to those in which clay as a material is rendered mute, its potential to elaborate material narratives entirely suppressed. While the relative position of a given work within such a spectrum would at one time would have carried definitive implications with regard to such categories as convention and rebellion or art and craft, today, as the varied work in Beyond the Vessel aptly attests, clay as a medium is arguably freer than it has ever been to simply facilitate creativity.

whole surface so what that means is that the gouache only goes in the lines, it just picks up the lines. I suppose the wax must glide over the top of the grooves. So on the final stages I’m trying to emphasise various parts of the pencil line and various parts of the drawing. It comes to a point where I’ll even use a very very fine number one paintbrush to actually paint in individual lines if I had to. At that point then, at that stage of the drawing, it slows right right down, and I can be messing around for several days, trying to get it adjusted. I suppose i’m trying to get to.. stillness or something, yes I’m trying to get a sort of calmness and stillness within the drawing even though its very busy I suddenly want to control that business, I’m not quite sure why but that feels right anyway.

whole surface so what that means is that the gouache only goes in the lines, it just picks up the lines. I suppose the wax must glide over the top of the grooves. So on the final stages I’m trying to emphasise various parts of the pencil line and various parts of the drawing. It comes to a point where I’ll even use a very very fine number one paintbrush to actually paint in individual lines if I had to. At that point then, at that stage of the drawing, it slows right right down, and I can be messing around for several days, trying to get it adjusted. I suppose i’m trying to get to.. stillness or something, yes I’m trying to get a sort of calmness and stillness within the drawing even though its very busy I suddenly want to control that business, I’m not quite sure why but that feels right anyway.

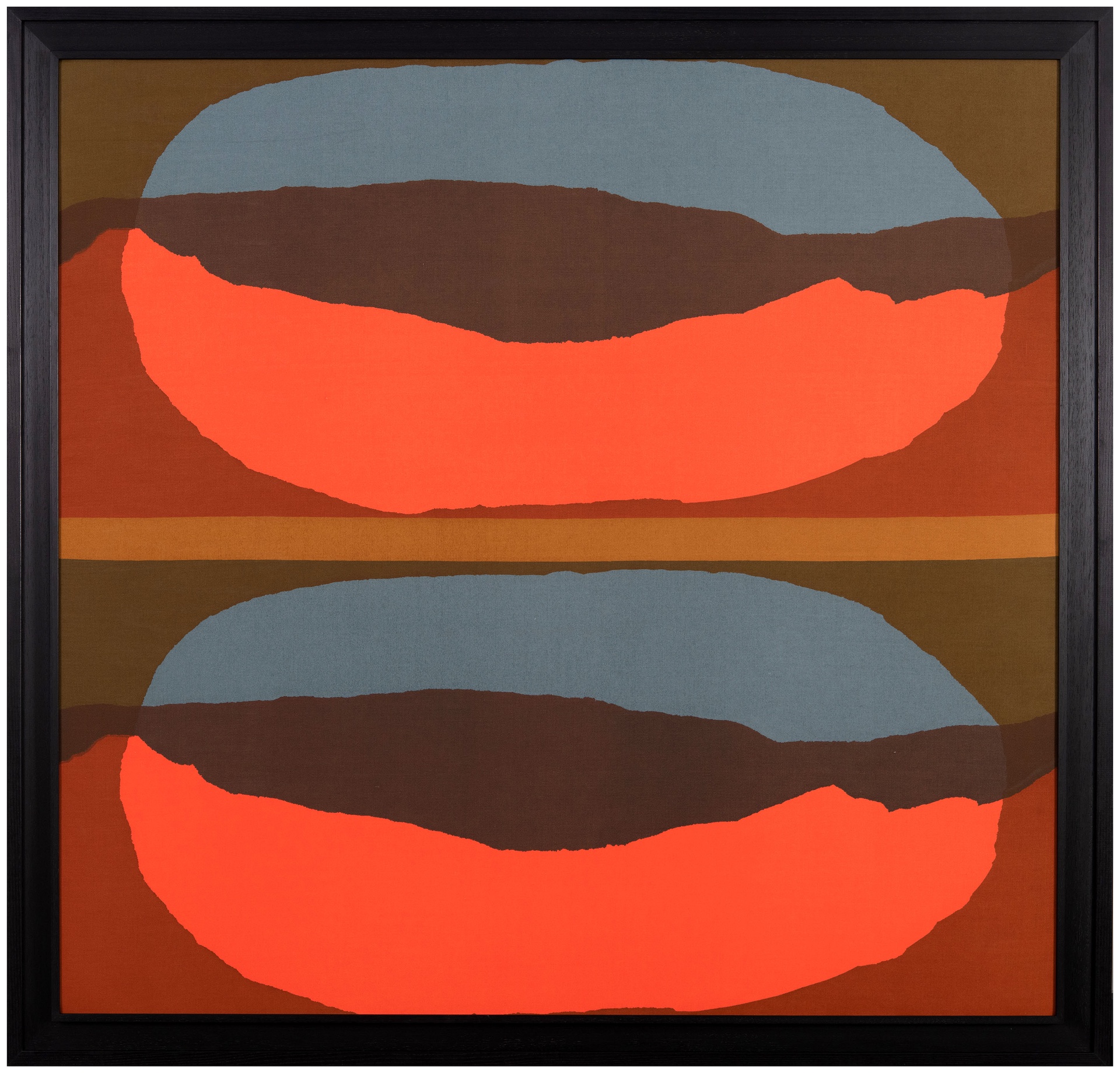

CP: Yeah, because, you mention the word restraint and you meant the square. It is a restraint but also it makes decision making a lot easier, otherwise theres always all those different sizes you can do. You can have a rectangle in all sorts of different proportions but there is a convenient side of things because as a maker of things, i’d rather call myself just a maker of things, as a maker of things there are so many choices and its actually quite important to reduce your choices. But there was a logic behind reducing choices to a square, well you’ve got the classic thing about the portrait and landscape isn’t it. Painting is always in a proportion of landscape or portrait but a square in neither so it has that great advantage, it is a very powerful structure and virtually nothing will break it down really so I’m constantly trying to break it down to a point where it just.. sometimes it may nearly disappear altogether but its got that nice tension about seeing how far you can go with a drawing. In terms of extending the drawing, not beyond the boundary and yet its still feels like a square even though the drawing escapes right the way to the edge of the piece of paper, you’ll still feel the square when it’s finished, I hope.

CP: Yeah, because, you mention the word restraint and you meant the square. It is a restraint but also it makes decision making a lot easier, otherwise theres always all those different sizes you can do. You can have a rectangle in all sorts of different proportions but there is a convenient side of things because as a maker of things, i’d rather call myself just a maker of things, as a maker of things there are so many choices and its actually quite important to reduce your choices. But there was a logic behind reducing choices to a square, well you’ve got the classic thing about the portrait and landscape isn’t it. Painting is always in a proportion of landscape or portrait but a square in neither so it has that great advantage, it is a very powerful structure and virtually nothing will break it down really so I’m constantly trying to break it down to a point where it just.. sometimes it may nearly disappear altogether but its got that nice tension about seeing how far you can go with a drawing. In terms of extending the drawing, not beyond the boundary and yet its still feels like a square even though the drawing escapes right the way to the edge of the piece of paper, you’ll still feel the square when it’s finished, I hope. HH: You gave a wonderful talk as part of the last exhibition with us in Wiltshire in the long gallery about drawing and that sort of immediacy of it and the importance of it as an action, as a way of mark making and the kind of accessibility of it as well as the fact that its sometimes not seen as the highest of art forms when actually I think, what amazing about your work, and I don’t know whether it’s the scale or the detail or the way that you make them, there’s something about the mark making its almost like listening to music, there’s a lot to be absorbed by and I suppose what’s strange about this exhibition is that people wont be seeing your works in real space. They will be experiencing them virtually which is a sort of departure because artists want people to stand in front of their work and I wonder whether there was any advice we could give to people looking at your work and maybe experiencing it for the first time through a computer screen.

HH: You gave a wonderful talk as part of the last exhibition with us in Wiltshire in the long gallery about drawing and that sort of immediacy of it and the importance of it as an action, as a way of mark making and the kind of accessibility of it as well as the fact that its sometimes not seen as the highest of art forms when actually I think, what amazing about your work, and I don’t know whether it’s the scale or the detail or the way that you make them, there’s something about the mark making its almost like listening to music, there’s a lot to be absorbed by and I suppose what’s strange about this exhibition is that people wont be seeing your works in real space. They will be experiencing them virtually which is a sort of departure because artists want people to stand in front of their work and I wonder whether there was any advice we could give to people looking at your work and maybe experiencing it for the first time through a computer screen. where it’s going to come out and that’s where the excitement is of creating anything. I obviously cant speak for anyone else but I do feel that that must be to a certain extent how it is because, in fact I remember someone recently who, she was doing something for the Tate, she said she’d got this great idea, and now she had to go an make it, well she didn’t really like the idea of making it. And it happens at colleges now, you’re meant to write it all down what you’re going to do and then you do it. Well that seems pointless. The great idea, to me, has to be modified by the physical facts of making and so if you just have an idea on paper and you totally translatephysical reality I’m not sure you’ve achieved very much, you might as well just have the idea on paper which is in other words just the concept. There’s nothing wrong with that, the conceptualists did that, but then im old school. You’re always taught that, you’ve got to let the material have some say in the matter when your making something.

where it’s going to come out and that’s where the excitement is of creating anything. I obviously cant speak for anyone else but I do feel that that must be to a certain extent how it is because, in fact I remember someone recently who, she was doing something for the Tate, she said she’d got this great idea, and now she had to go an make it, well she didn’t really like the idea of making it. And it happens at colleges now, you’re meant to write it all down what you’re going to do and then you do it. Well that seems pointless. The great idea, to me, has to be modified by the physical facts of making and so if you just have an idea on paper and you totally translatephysical reality I’m not sure you’ve achieved very much, you might as well just have the idea on paper which is in other words just the concept. There’s nothing wrong with that, the conceptualists did that, but then im old school. You’re always taught that, you’ve got to let the material have some say in the matter when your making something.

Chagué’s modus operandi unselfconsciously employs contemporary strategies of interactivity, just as his old teacher the great potter Michael Cardew embraced esthétique relationnelle long before the term was invented. Chagué once organised a community dinner and concert, with 250 people eating off his plates, each one playfully inscribed assiette en glaise. Like Cardew’s Wenford Bridge Pottery in Cornwall (carried on after his death in 1983 by Cardew’s son Seth but now completely gone) Chagué’s house is a collective where he, his children and his friends, students and helpers eat and discuss together at a long wooden table. Chagué’s particular choice of raw clay, is brought as dug from a village near the pottery town of La Bourne. At high temperature it acts temperamentally. Forms split and shapes sag. This is not a concern for Chagué, indeed he relishes the uncertainty of the ceramic process, finding uncertainty a useful provocation –in French a word that has powerful artistic associations. The clay is not purchased for its efficiency but for its tactility and materiality. He disregards conventional ceramic technology, and all his work is fiercely sculptural. It is therefore surprising to discover that all his pieces are built from thrown elements. The discipline of the potter’s wheel with its drive to repetition and symmetry appears remote from the dramatic, fractured nature of these complex objects.

Chagué’s modus operandi unselfconsciously employs contemporary strategies of interactivity, just as his old teacher the great potter Michael Cardew embraced esthétique relationnelle long before the term was invented. Chagué once organised a community dinner and concert, with 250 people eating off his plates, each one playfully inscribed assiette en glaise. Like Cardew’s Wenford Bridge Pottery in Cornwall (carried on after his death in 1983 by Cardew’s son Seth but now completely gone) Chagué’s house is a collective where he, his children and his friends, students and helpers eat and discuss together at a long wooden table. Chagué’s particular choice of raw clay, is brought as dug from a village near the pottery town of La Bourne. At high temperature it acts temperamentally. Forms split and shapes sag. This is not a concern for Chagué, indeed he relishes the uncertainty of the ceramic process, finding uncertainty a useful provocation –in French a word that has powerful artistic associations. The clay is not purchased for its efficiency but for its tactility and materiality. He disregards conventional ceramic technology, and all his work is fiercely sculptural. It is therefore surprising to discover that all his pieces are built from thrown elements. The discipline of the potter’s wheel with its drive to repetition and symmetry appears remote from the dramatic, fractured nature of these complex objects. In this exhibition we are both guided and playfully confused by the titles that Chagué has given each individual piece. Some come under the category Albarelle and indeed these upright forms faintly echo their namesake, the highly collectible Renaissance maiolica jars known as Alberelli. But these are jars turned biomorphic and matched by an equally haunting series that come under the rubric Blastoïde –a poetic reference to the fossils of long extinct seabuds, once anchored to the sea floor. Both sequences belong equally to the natural and made world. They are the work of Chagué’s hand while offering echoes of primordial growth during some remote period –Devonian or Silurian perhaps –long before humans walked the earth. At the same time these are highly sophisticated examples of ceramic facture that allow chance to play its part but which also testify to a long-learnt control over clays bodies and glaze materials. And of course they are remarkable because they braid ceramic and sculpture. Chagué’s work has deep roots in ceramic history –but that is not the whole story. Rainer Maria Rilke, writing in 1903, explained that sculpture was ‘a complete thing about which one could walk, and which one could look at from all sides.’ He concluded that sculpture also had ‘to distinguish itself somehow from other things, the ordinary things which everyone could touch’. Ceramics, of course, belongs in both worlds described by Rilke –that of the ‘complete thing’ and of ‘ordinary things’. What Thiébaut Chagué gives us are sculptures that everyone can touch.

In this exhibition we are both guided and playfully confused by the titles that Chagué has given each individual piece. Some come under the category Albarelle and indeed these upright forms faintly echo their namesake, the highly collectible Renaissance maiolica jars known as Alberelli. But these are jars turned biomorphic and matched by an equally haunting series that come under the rubric Blastoïde –a poetic reference to the fossils of long extinct seabuds, once anchored to the sea floor. Both sequences belong equally to the natural and made world. They are the work of Chagué’s hand while offering echoes of primordial growth during some remote period –Devonian or Silurian perhaps –long before humans walked the earth. At the same time these are highly sophisticated examples of ceramic facture that allow chance to play its part but which also testify to a long-learnt control over clays bodies and glaze materials. And of course they are remarkable because they braid ceramic and sculpture. Chagué’s work has deep roots in ceramic history –but that is not the whole story. Rainer Maria Rilke, writing in 1903, explained that sculpture was ‘a complete thing about which one could walk, and which one could look at from all sides.’ He concluded that sculpture also had ‘to distinguish itself somehow from other things, the ordinary things which everyone could touch’. Ceramics, of course, belongs in both worlds described by Rilke –that of the ‘complete thing’ and of ‘ordinary things’. What Thiébaut Chagué gives us are sculptures that everyone can touch.