“Heat cannot be separated from fire, or beauty from The Eternal”

-Dante Alighieri

Glass making is a dialogue between many elements and many people; it requires patience, creativity and teamwork. Dialogues open new avenues of potential exploration between those that enter them. There is a clear parallel between two Dantes who set themselves apart from their contemporaries through pursuing revolutionary paths in their respective creative fields. The first Dante is Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) who developed the dynamic possibilities of literature in the Italian Renaissance through works such as The New Life and Divine Comedy. The heir to Aligheri’s maverick spirit is the second Dante, Dante Marioni (born 1964), one of the leading figures in contemporary American glass, who combines the same elements that their Florentine namesake put to the page into their own art: heat, fire, beauty, and The Eternal to create works that move beyond the expected and attempt to define and represent our own era. Dante Marioni is realising some of the most progressive and technically perfect vessels of our time.

Dante Alighieri’s work Divine Comedy tells the story of Alighieri’s imagined long journey through an Inferno (hell) to Paradise (heaven). Dante Marioni goes on a similar journey in their practice, manipulating through their singular skill the transformation of a heated form of glass, that is removed from the bowels of raging inferno, into a clear and cool structure- the antithesis of what it was, representing the magnificence of paradise. Glassblowing is the act of combining seemingly impossible techniques to transform and manipulate molten liquid into its antithesis without direct touch: a cool solid formation. This process can be temperamental, but the final product will never reveal the strife, skill, and strength that went into its production.

HEAT:

Glass has been desired as a material for thousands of years, dating back to Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, with some early pieces being created from 3600 BCE. Under the dynamic system of trade established throughout the Roman Empire, glass spread across the globe, leading to glass objects ending up in many unexpected places, including in Han Dynasty (202 BCE- 220 CE) Chinese tombs. After the fall of the Roman Empire glass production devolved to independent productions revolving around local techniques. It wasn’t until the 14th century when the Venetians pioneered techniques to produce tough and transparent glass that a rightful heir to the glass empire emerged – Venetian glass, complete with engaging forms, textures, and colour, became a desired product internationally. The Venetian way of life was inextricably linked to glass, with it being central to the economy, to such an extent that if a glassblower left Venice without permission thier family would be imprisoned until their return, and an assassin would be dispatched to stop the spread of glass related secrets if a glassblower failed to return. Despite being removed to the island of Murano (by a 1291 decree to prevent fires across Venice), glassblowers held a prestigious position in society that enabled special privileges, such as being able to marry into nobility, carrying extra swords, and the acquisition of wealth. It is from this dynamic legacy that contemporary glassblowing hails; just as the Dante Aligheri’s Inferno was filled with intrigue and drama, so too was the glass producing world.

Seattle, where Dante is based, is the centre of glassblowing in America. This area is infused with the same passion for glass that has been found in Murano for almost 1000 years. It was the vision of a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor, Harvey Littleton, to bring glassblowing out of the factories and into the studio and form a hub of artisans that would experiment and push glass to new heights. In 1962 Littleton created the first collegiate glass course in America and prompted a new wave of glass societies and locations for artisanal glass to develop. One of these was the Pilchuck Glass school, founded in 1971 by Dale Chihuly, was created as a space to encourage experimentalising in glass and yet was firmly based on mastering complex Muranese skills such as caning as Chihuly had trained in Venice. The methodology of teaching was based around artists teaching artists, which enabled a synthesis of techniques and ideas to develop out of this centre, this in turn solidified Seattle’s throne as the glass producing capital.

FIRE:

Dante Marioni has been at the forefront of artistic glass since the age of nineteen, pushing for new forms, colours, techniques, and inspiration. The fire to work with glass came from Dante’s father, Paul Marioni. Paul, a fellow glassblower, began working with glass in about 1972; for Dante when these early works of glass art were brought home it was a revelation. To be viewing glass not just as a something that could be handmade but even devoid of practicality was something refreshing and inspiring. This led Dante to work at a local glass blowing factory in Seattle as a teenager, and eventually training under the Muranese master Lino Tagliapietra and Americans Benjamin Moore and Richard Marquis. This transcontinental training places Dante firmly in the centre of contemporary glass, as well as continuing the legacy of Venetian Muranese glass. Dante’s ability was further cemented at the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington, where Paul Marioni also taught.

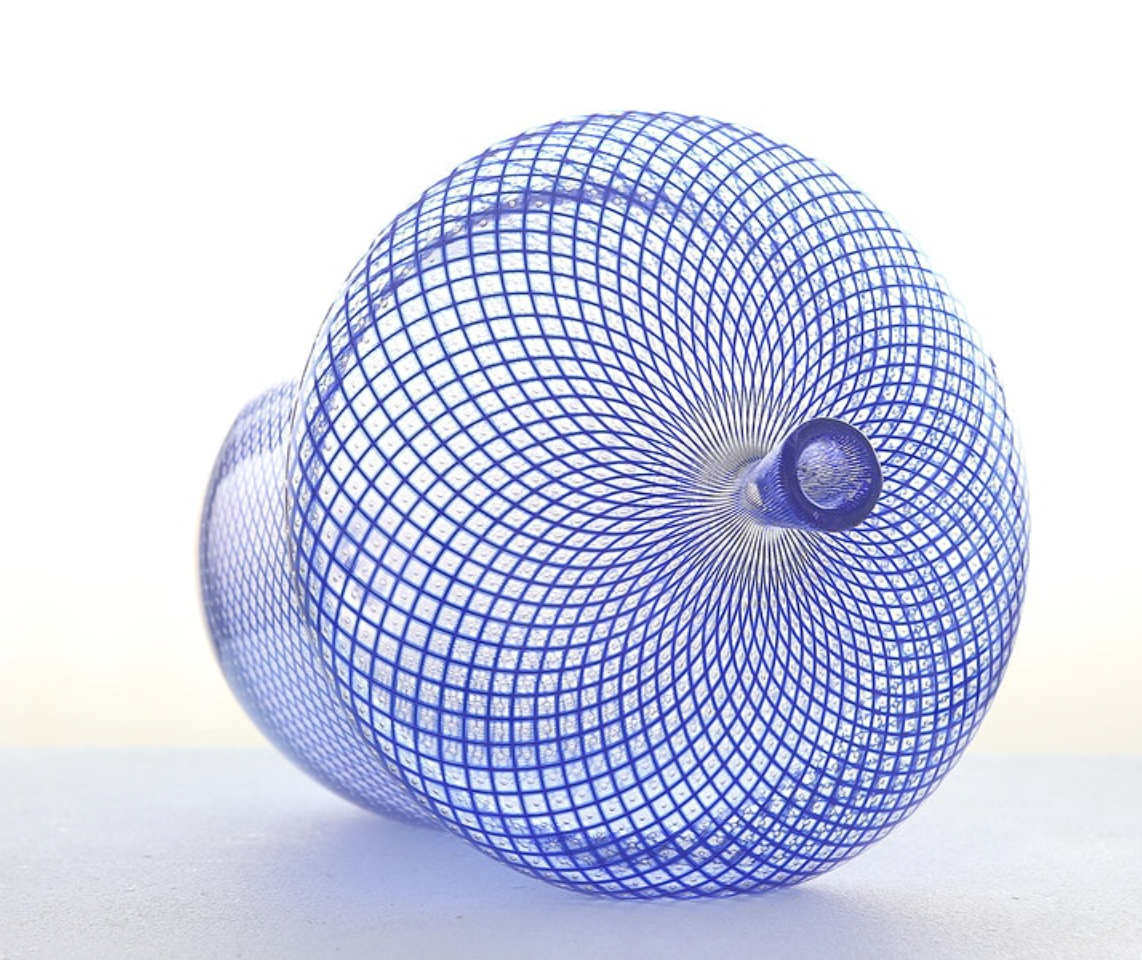

For Dante, this fire has never been put out. There is a continued desire to prefect, master, and develop as many techniques with glass as possible. This has led Dante to push for new forms and designs in their oeuvre. One of these designs embodies this fire within: the acorn. Dante was infatuated with acorns, something that could fall from the tree without being damaged and subsequently grow into something steadfast and strong. In a similar way Dante has grown in confidence and ability to create a huge variety of works. Notably Dante’s acorns are executed in reticello, one of the most complex forms of Venetian glass. Reticello requires a glassblower to create two forms of identical shape based around cylindrical canes of glass, these canes are then fused together in opposing directions to create a lattice effect, betwixt each lattice a delicate air bubble should appear to create a visual dot matrix pattern. Through the use of this technique Dante’s acorns proclaim themselves not to be naïve youths with potential for greatness, but rather prodigies of brilliance with advanced knowledge and abilities. Dante works as a single-handed artist, eschewing large teams, and places their own hand, breath, and iconography at the centre of each piece.

BEAUTY:

The beauty of Dante’s glass lies in the manner it transcends time. When Dante was first exposed to glass and its potential in the 70s, the mode was for artful blobs; these freeform shapes held little allure for Dante. It was witnessing the skill of Moore, who was able to produce a symmetrical on-centre vessels, that led Dante to explore more formalised shapes. Dante’s inspiration reaches back to classicism, with the formation of long necked vessels and structured bodies. When Dante, at the age of 23, unveiled the ‘Whopper’ series a shift in glass design sensibilities occurred. This series of enlarged and boldly coloured vases recalled the development of classical appreciation that occurred during the Renaissance. Reminiscent of vessel forms found in Parmigianino’s seminal work ‘Madonna of the Long Neck’, Dante’s classical forms have an iconographic history of elegance, refinement, humanist ideals, and a connection with our shared human existence. Dante’s elegant forms in their exaggerated scale create an emulation of the human body and allow the vessels to take on a personality of their own- something that the viewer can engage with.

Large glass forms offer new and intriguing challenges to the creator, glass can only be formed in relation to the size of the kiln available. This challenge presented by the physical constrains of manufacture allow Dante’s monumental glass vases to sit at the height of glass technicality. These vases join the realm of other monumental glass greats such as Dale Chihuly, an American glass blower whose work has been exhibited at Kew Gardens (2019) and the Victoria & Albert Museum (2001). These large works of Chihuly are more free form than Dante’s, but only serve to demonstrate the strict structural beauty that Dante creates through focusing closely on proportionality and line. Chihuly, through working with a team in a more hands-off conceptual approach, has created dynamic works that visually provoke and questions the expectations of form in glass. For Dante, the body and form are similarly integral to the aesthetic impact; with each work provoking through design but also pushing the boundary of physicality and the scale that a single glass artisan can produce rather than a team. Both artists clearly overlap in their appreciation of colour and technique and clearly display an aptitude for creating lavish colour stories that electrify their setting.

THE ETERNAL:

Carlo Scarpa, the notable 20th century architect, is one of the most significant names in the modern history of glassblowing. Working in many Venetian glass works through the early part of the 1900s. Scarpa, not unlike Dante, pushed for a revolution in the capabilities of glass design. Scarpa married two iconic crafts of Venice, glass and mosaic, in one with their Roman Murrine series that was unveiled in 1936. This technique, of combining small squares of glass together before being blown into fantastic shapes, was one that Dante spent years perfecting; it is through this Mosaic series that Dante expresses their connection with a legacy of Murano, Venice, Roman, and earlier glass cultures.

Through the ‘Vessel Displays’ series, Dante also explores the concept of the Eternal by engaging in the universal human activity of collecting and display. This form of displayed collecting stretches back to the Renaissance and the rise of the Wunderkammer, or Cabinet of Curiosities. These Wunderkammer were designed to allow the owner or viewer a chance to explore and understand the physical universe both natural and synthetic. Collecting is an innate activity found in every culture, making it one of the few shared activities that has existed throughout the whole of human history. For these ‘Vessel Displays’ Dante plays with the concept of collecting and the history of Wunderkammer. Dante creates a variety of different forms that display the variability and flexibility of glassblowing, Dante’s own dynamic range, and unveils the extraordinary universe of glass: with some angular; some curvilinear; some contemporary in form, and some historic in shape. By creating spaces that catalogue and explore this concept in glass we see an exciting look into aesthetics, the universal, and human achievement. Wunderkammer displayed the true variety, versatility and history of the natural and synthetic world and glass, rather poetically, is itself the mastery of natural elements transformed into the synthetic, and when presented in this manner, with its diverse history in tow, glass is heightened to its most symbolically potent form.

The Eternal is something difficult to capture and express; yet Dante, with their understanding of the lineage of glass forms and techniques manages to marry this illustrious past with the experimental verve of the now. This walking this line of historicism and contemporaneity is not a simple accomplishment, rather it speaks to the artistic vision and capability of one of the greatest living glass artists.

We are excited to offer our visitors a glimpse into the universe of Dante Marioni at Messums Yorkshire in our upcoming exhibition.