John Beard is an artist who has led an adventurous life, leaving Britain in the early 1980s to teach in western Australia, then settling in Sydney, while at the same time showing his work all over the world — in New York and Delhi, Madrid, Melbourne, New Zealand, London, Lisbon and St. Ives.

I first got to know him in the late 1990s, when a work of his, Wanganui Heads, was included in an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, Painting the Century, held to celebrate the millennium in 2000. In 2007, he won the Archibald Prize, the leading prize for portraiture in Australia and, in some ways, the world, since it is a prize of such long-established prestige, centre stage in the Australian art world in a way that the BP Portrait Award never has been. But he is not a portrait painter, any more than he is a landscape painter. He’s a painter of disappearing and sometimes ephemeral appearances — images which hover in a space somewhere between realism and abstraction, half real, half remembered, highly composed, but, at the same time, loosely brushed and ill-defined, not as seen, but touched, transmuted, as the ghost of physical appearances.

In the midst of this peripatetic and transient life, he arranged to rent a cottage in October 2020 in the heart of the Wiltshire countryside, due west of Salisbury, looking across fields and farmland towards a line of hills of the south Wiltshire Downs. Then came another COVID lockdown. He and his wife, Wendy, were trapped in Wiltshire by the epidemic, not allowed to meet people, not allowed to leave. They had only the view of the distant hills for company.

Out of this period of being stuck in the English countryside, he has produced a body of work which is intensely atmospheric and solitary, the landscape of fields and hills half seen, half absorbed into his imagination and then idealised into views of the snow and the mist, the wintry hills and the outlines of the distant trees along the horizon and the ploughed-up fields in diagonal lines stretched across the foreground, sometimes covered in a light dusting of snow.

He works in watercolour, too, as did Turner: watercolour which is such a wonderful medium for the depiction of atmosphere, because it is done at speed and cannot be over-worked. Again, you see the distant line of hills trailing off into the left-hand horizon; the evening light as the trees and fields merge, the only definition provided by the line of trees on the horizon, or, occasionally, one lone tree in the middle distance, providing an incident in an otherwise featureless landscape. Sometimes you can feel him sitting down and wanting to catch the last of the evening light in the watercolour.

Landscape is a difficult genre in the modern world, as is portraiture. It’s been too hackneyed, perverted by the ease and instantaneity of photography, so that it is hard to convey the restfulness of nothing, the subtleties of light, so ethereal, so liquid and imprecise.

Hovering, shimmering, transient. This is not conventional English landscape, but is instead both ordinary and epic at the same time; one piece of countryside, the south Wiltshire downs, seen over and over again as the months of COVID meant that there was no possibility of further exploration, only of enjoying and appreciating what is there — looking at it, thinking about it, visualising it, recording it, always the same, which for a period of time, six months, was all that he had to depict, no people to talk to, just fields and the distant line of downs.

Sir Charles Saumarez Smith CBE is a British cultural historian specialising in the history of art, design and architecture. He was the Secretary and Chief Executive of the Royal Academy of Arts from 2007 until 2018.

By Catherine Milner

Satire has always been a key feature of British art; from Hogarth to Spitting Image, Gillray to Banksy, artists in this country have for centuries lampooned hypocritical politicians or dim-witted dignitaries with glee.

In this respect, Stephen Dixon stands in an heroic tradition. But perhaps what makes him unusual is the scope of his savagery.

Unlike those artists from the past who mostly attacked British statesmen and British aristocracy while occasionally swiping at the French or Americans, Dixon takes aim at leaders from across the globe, from Donald Trump to Aung Sang Suu Kyi or when he was alive, Saddam Hussein.

His work targets the oil industry, the refugee crisis, slavery and asylum issues, echoing in his range, our change from imperialists to political activists and sometimes, bungling interventionists.

Born in 1957 in Peterlee in County Durham – a post-war town named after a social reformer bent on ending squalor – Dixon was steeped in politics from an early age; he is the son of a teacher who was an active member of the Labour Party and the grandson and nephew of a tribe of coal miners.

‘From the start I was never interested in making functional pieces, and more interested in telling stories and making statements’ he says.

One of the highlights of this show is a series of oil cans made in clay highlighting the folly of the Iraq War.

Although the same size as a real oil can, Dixon’s are wonky and plastered with images of Frankenstein – ciphers for the monster he thinks the West created in the Middle East with their initial support of Saddam Hussein – as well as icons of American audacity and derring-do like Charlton Heston pictured on a gas-guzzling motorbike.

Robustly modelled, with handles like cuffed ears, spouts like snouts and featuring an array of jaunty clay odalisques lying on top, these vessels have a strong physical presence that is complemented by the gauzy, photographic images wrapped like clothes around their trunks.

In works as bitingly accusatory as they are friendly to look at, icons of Eastern culture like the Kama Sutra, the tombs at Petra or the defaced Bamiyan Buddhas are superimposed with highlights of those from the West; the Laocoon, Michelangelo’s David and flocks of US fighter jets.

‘I want to draw attention to the highest and lowest forms of civilization in each kind of culture,’ explains Dixon.

Although more of a teapot than an oil canister, a particularly caustic piece in this show is a vessel decorated with a drawing of Diana, Princess of Wales presented as the Hunted rather than the Huntress with antlers on her head. Hounded by dogs Dixon has graphically drawn her womb – making the point that her main function was to bear an heir to the throne.

Another remarkable work decorated with a picture of a teenage girl brandishing a Kalashnikov is called 21 Countries – a reference to the number of nations bombed by the Americans since the Second World War.

It is not just America that seems to provoke Dixon’s ire, however. Recently he has turned his attention to the migrant crisis, seeing a parallel between the journey of Majolica – the tin glazed wares – and that of refugees.

Originally from North Africa Majolica spread through Italy, France and the Netherlands before finally arriving in England in the form of English Delftware.

In this exhibition are a series of tin-glazed plates which feature a dazzling array of contemporary hieroglyphs – both positive and negative. In no particular order appear some handcuffs, the lion and the unicorn coat of arms, a dominatrix holding a whip, Homer Simpson holding a trident, Donald Trump as a winged dinosaur; Carl von Ossietzky winner of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize and perhaps most fittingly of all, a double portrait of Pandora, opener of the famous Box.

Having studied Fine Art at Newcastle University and Ceramics at the Royal College of Art in the 1980’s, Dixon became Senior Research Fellow in Contemporary Crafts at Manchester School of Art in 2003, becoming Department head and Professor of Contemporary Crafts since 2007.

Doggedly committed to a form of art that has been pretty unfashionable during the last fifty years, he has ploughed his own furrow with exceptional zeal, maximising the impact of his work by learning how best to apply water-based screen printed transfers to ceramics – attending universities and colleges in Edinburgh, Cork, Beirut, even Australia to become one of the world leading practitioners in this technique.

Dixon and Carol McNicoll – another questioning ceramicist also in this exhibition – and the likes of Grayson Perry and Edmund de Waal prove beyond doubt that contemporary painters, rightly lauded for their powerful polemic do not have the stage to themselves any more.

The difference is that contemporary ceramic can form the centrepiece of your table as well as your wall.

‘My career as a maker is defined by a commitment to politically engaged practice, and a belief in the power of craft to inform the public imagination and to make a difference,’ says Dixon.

In its technical skill, aesthetic and sensual allure and powerful narratives, Dixon’s work engages us on many levels chief of which seems to have been as a harbinger of the formidable new political age we have suddenly entered.

by Catherine Milner

Last November a record price for ceramic – £240,000 – was set for a pot by Magdalene Odundo, one of a group of ceramic artists that Messums are showing in March.

The clay pot has been a means of human survival for thousands of years; its decorations, engravings and embellishments offering an intimate record of how people have lived.

And although the market for the finest of ceramics still lags way behind that of the ‘fine art’ market and artists like Jeff Koons whose stainless steel Rabbit sculpture sold a couple of years ago for $91 million, the fact that they are being valued increasingly highly tell us a great deal about the seismic shift our culture is undergoing.

One might have expected a humble vessel made simply of clay to have become artistically obsolete with such a wide variety of technical innovations and novel materials available to artists.

But quite the contrary.

To generations brought up within an education system that prioritises working on computers rather than with their fingers and imagination, clay can seem exciting – almost anarchic.

Clay vessels reconnect the viewer with the ground beneath our feet; perfect ciphers for our new awareness of the fragility of the earth that like a pot itself, must be handled with care.

Over the last five years Messums has been tracing the evolution of this new movement with as many as thirty exhibitions and festivals focused on clay, culminating last year in Beyond the Vessel, one of the biggest exhibitions of contemporary clay sculptures to have been held anywhere in the world.

Shown firstly at the Mesher Gallery in Istanbul and then at Messums in Wiltshire, the exhibition brought together thirteen sculptors from seven European countries – each expressing different aspects of European myths and folklore in clay.

This exhibition brings us back to the vessel and highlights the pivotal role that the Royal College of Art in London has played in leading the renaissance of art using clay. Almost all the artists in it went to the RCA in the 1970’s ; a place that coupled the teaching of stringent technical disciplines with lively intellectual debate resulting in works that are exquisitely executed with compelling narratives to boot.

Having been educated in Kenya, the ‘narrative’ of Odundo’s work lies more in the shape and style of her works than any explicit drawings or words but a narrative is there nonetheless.

All her pieces, including the two we have on display, reveal the natural shapes of the human body – the pot belly, the curves of the spine, the hair – abstracted, burnished and formed into vessels.

A perfect piece of abstract art embodied in the most ancient form of utility.

‘Using the human form is a very natural way of sculpting with clay’ she says. ‘After all, the Bible says that God took clay and used it to form man. It’s something that is within our culture. The first thing you do as a child is get a piece of clay, squeeze it into your hand, add bits and pieces, then draw an eye or a mouth on to it. Clay automatically lends itself to making. It is embodied into the motion of making a body, a person.’

There are elements of human form in the works of Alison Britton too. Not only in the jug eared handles of her platters or the jaunty arms of some of her pots but in their uneasy stances; their craning necks or lopsided shoulders making them studies in the awkwardness of human beings for which clay acts as such a wonderful simulacrum. Not for her symmetrical forms and mathematical precision of some of the other pots in this show, but intuitive ‘flicks, squirts and slips.’

‘An unfired pot is naked; its needs something happening to it, like a body needs a dress,’ she says, challenging herself to make the painting on a pot in an unpremeditated fashion, less like patterning and more like an abstract painting in which the canvas is slabs of clay.

In Japan and Korea, ceramics represent a zenith of cultural expression, thanks to their ability to convey unique styles, customs, and politics within their form.

The Confucian ideals of frugality and purity has become a defining symbol of Korean and Japanese potters and running in tandem with our show of pots by British makers are works of the most exquisite perfection by Korean master Ree Soo-Jong and next month, by the Japanese artist, Makoto Kagoshima. A British equivalent is the work of Martin Smith, whose early works were large raku bowls which were precise and geometric, departing from the tradition of Japanese raku but keeping nonetheless their sense of purity.

His works in this exhibition play with perspective and reflection, surface and depth. Inspired by architecture they turn away from the malleability of clay, forcing it instead into angles of geometric precision.

Smith is Senior research Fellow of Ceramics at the RCA, where he is investigating

the ‘Potential of the Digitally Printed Ceramic Surface,’ and many of his works mimic other materials like wood, silver or gold in a way that clay objects have for centuries been skeuomorphs.

Although Steven Dixon has made several research trips to Japan, his way of working could not be more different, manifesting one of the enduring characteristics of British art – satire. From Hogarth to Spitting Image; Gillray to Grayson Perry, the British have always used wit to puncture authority and lampoon social vices.

He is currently working on a project that traces the history of Majolica; the type of tin-based glaze that is best known as coming from Italy but in fact originated in North Africa which spread throughout Europe until it appeared in England in the shape of English Delftware; using this trajectory of travel as a metaphor for the journey undertaken by refugees.

On one of his plates Mona Lisa brandishes a Kalashniko; on another, Michaelangelo’s David is woven with images of Palmyra after it was ruined by terrorists; totems from both ‘the highest and lowest points of civilisation,’ he says.

There are also a series of magnificent oil cans by Dixon made of clay, each standing at least 60 cms high and therefore actual size. They were made in the 1990’s during the time of the Iraq Wars and expose the hypocrisy of the West as it created a Frankenstein’s monster in the shape of Saddam Hussein and turned The Holy Land into a group of basket states.

Closer to home are the satirical works of Carol McNicoll, which include a ‘Non Socially Distanced’ Toby jug plastered with images of her friends, dancing, abseiling and sitting in the pub. She has also made a vase dedicated to the area of North London in which she lives called The Heath which subverts its reputation as a place for gay men to congregate by featuring an image of a bewigged and stockinged 18th century courtly gentleman bowing in front of a lady.

Back in ancient Greece pots recorded all sides of life from drinking games to gladiatorial wrestling matches to combing your hair. Thousands of years before that, they told us how Neolithic man worshiped, cooked and travelled around meeting with other tribes.

It is this ancestry of pots; their familiarity to us as domestic ally coupled with them being the nearest equivalent to our own bodies as vessels for our souls, that makes them particularly compelling at such a time of threat.

RELATED LINKS:

An essay by Catherine Milner

‘The voyage of discovery is not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes,’ said Marcel Proust and at the moment, the effects of that thought can be seen as not just philosophical but also practical.

In the absence of ready and immediate travel many of us have started to enjoy what we see around us; discovering a new Eden in what we have already before our eyes.

Years of metropolitan culture; going to nightclubs, restaurants, shops, galleries and increasingly arcane coffee shops seem to have been exchanged in the blink of an eye by such prosaic activities as walking and gardening.

The landscape, so long seen as a backdrop to our lives, has taken centre stage; Nature and its wonders, objects of curiosity increasingly demanding our attention and being talked about.

So, it is no surprise that a new school of landscape painters has emerged. In truth it has always been there but, obscured by the noise surrounding the industrial and technological advances we have made, we did not much hear its quiet beat.

Britain’s landscape painting tradition – much like the landscape itself – is one of the best preserved in the world.

It has emerged and disappeared as a genre every few decades since the 18th century when painters like JMW Turner or Thomas Gainsborough first began to celebrate it.

The Pre-Raphaelites; the Newlyn School, to some extent the Bloomsberries, the Nash brothers, the St Ives Group and latterly artists like David Inshaw and Michael Andrews have all sought to express the charm of our island, often following or coinciding with a period of intense industrialisation or war; William Morris’ wallpaper designs featuring banks of peonies or John Nash’s pre-war paintings of bucolic haystooks are just some examples of many escapes into arcadia.

And although landscape painting has been out of the mainstream for years there have been signs even before the onset of this pandemic, with technology was riding high and society increasingly atomised, that the embers of our love affair with landscape had begun to smoulder anew.

Leading painters, Hurvin Anderson, Peter Doig and Luc Tuymans have made landscape a central feature in their work for decades but often at a distance, in a slightly alienated way.

Now, as our roster of new exhibitions show, the landscape is seen as welcoming – not bleached of its colour, inpenetrable or fenced off but drawing us in, reminding us that we are at one with it.

Messums’ exhibitions this winter give us many new perspectives on the landscape; all through the medium of paint, that – much like landscape – comes in and out of fashion but in the end, scotches all rivals.

Richard Hoare’s pictures of Wiltshire and Dorset speak of the light behind all we see; the light that leads to photosynthesis, creating leaves on the trees and fostering all life. He depicts a world in constant motion – fluttering with life – capturing the abundance and fruitfulness of the southwest of England.

Constable once said that the sky sets the tone for any landscape painting and this is the striking feature of paintings by Hannah Mooney; her rich peat-coloured, crepuscular paintings of the lakes of County Mayo and the West of Ireland have a dark romanticism and contrast with the diaphanous, gossamer-thin watercolours of northern Italy by another of our rising stars, Francesco Poiana.

Situated in a 13th century medieval wooden barn constructed from vast trunks of elm and oak Messums Wiltshire can sometimes feel akin to being in a big forest. This year the paintings, more than ever, feel as if they are the lights.

Image 2. Detail of ‘Trees by Lake at Night – Fonthill’, Monotype Drawing by Richard Hoare

“Heat cannot be separated from fire, or beauty from The Eternal”

-Dante Alighieri

Glass making is a dialogue between many elements and many people; it requires patience, creativity and teamwork. Dialogues open new avenues of potential exploration between those that enter them. There is a clear parallel between two Dantes who set themselves apart from their contemporaries through pursuing revolutionary paths in their respective creative fields. The first Dante is Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) who developed the dynamic possibilities of literature in the Italian Renaissance through works such as The New Life and Divine Comedy. The heir to Aligheri’s maverick spirit is the second Dante, Dante Marioni (born 1964), one of the leading figures in contemporary American glass, who combines the same elements that their Florentine namesake put to the page into their own art: heat, fire, beauty, and The Eternal to create works that move beyond the expected and attempt to define and represent our own era. Dante Marioni is realising some of the most progressive and technically perfect vessels of our time.

Dante Alighieri’s work Divine Comedy tells the story of Alighieri’s imagined long journey through an Inferno (hell) to Paradise (heaven). Dante Marioni goes on a similar journey in their practice, manipulating through their singular skill the transformation of a heated form of glass, that is removed from the bowels of raging inferno, into a clear and cool structure- the antithesis of what it was, representing the magnificence of paradise. Glassblowing is the act of combining seemingly impossible techniques to transform and manipulate molten liquid into its antithesis without direct touch: a cool solid formation. This process can be temperamental, but the final product will never reveal the strife, skill, and strength that went into its production.

HEAT:

Glass has been desired as a material for thousands of years, dating back to Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, with some early pieces being created from 3600 BCE. Under the dynamic system of trade established throughout the Roman Empire, glass spread across the globe, leading to glass objects ending up in many unexpected places, including in Han Dynasty (202 BCE- 220 CE) Chinese tombs. After the fall of the Roman Empire glass production devolved to independent productions revolving around local techniques. It wasn’t until the 14th century when the Venetians pioneered techniques to produce tough and transparent glass that a rightful heir to the glass empire emerged – Venetian glass, complete with engaging forms, textures, and colour, became a desired product internationally. The Venetian way of life was inextricably linked to glass, with it being central to the economy, to such an extent that if a glassblower left Venice without permission thier family would be imprisoned until their return, and an assassin would be dispatched to stop the spread of glass related secrets if a glassblower failed to return. Despite being removed to the island of Murano (by a 1291 decree to prevent fires across Venice), glassblowers held a prestigious position in society that enabled special privileges, such as being able to marry into nobility, carrying extra swords, and the acquisition of wealth. It is from this dynamic legacy that contemporary glassblowing hails; just as the Dante Aligheri’s Inferno was filled with intrigue and drama, so too was the glass producing world.

Seattle, where Dante is based, is the centre of glassblowing in America. This area is infused with the same passion for glass that has been found in Murano for almost 1000 years. It was the vision of a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor, Harvey Littleton, to bring glassblowing out of the factories and into the studio and form a hub of artisans that would experiment and push glass to new heights. In 1962 Littleton created the first collegiate glass course in America and prompted a new wave of glass societies and locations for artisanal glass to develop. One of these was the Pilchuck Glass school, founded in 1971 by Dale Chihuly, was created as a space to encourage experimentalising in glass and yet was firmly based on mastering complex Muranese skills such as caning as Chihuly had trained in Venice. The methodology of teaching was based around artists teaching artists, which enabled a synthesis of techniques and ideas to develop out of this centre, this in turn solidified Seattle’s throne as the glass producing capital.

FIRE:

Dante Marioni has been at the forefront of artistic glass since the age of nineteen, pushing for new forms, colours, techniques, and inspiration. The fire to work with glass came from Dante’s father, Paul Marioni. Paul, a fellow glassblower, began working with glass in about 1972; for Dante when these early works of glass art were brought home it was a revelation. To be viewing glass not just as a something that could be handmade but even devoid of practicality was something refreshing and inspiring. This led Dante to work at a local glass blowing factory in Seattle as a teenager, and eventually training under the Muranese master Lino Tagliapietra and Americans Benjamin Moore and Richard Marquis. This transcontinental training places Dante firmly in the centre of contemporary glass, as well as continuing the legacy of Venetian Muranese glass. Dante’s ability was further cemented at the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington, where Paul Marioni also taught.

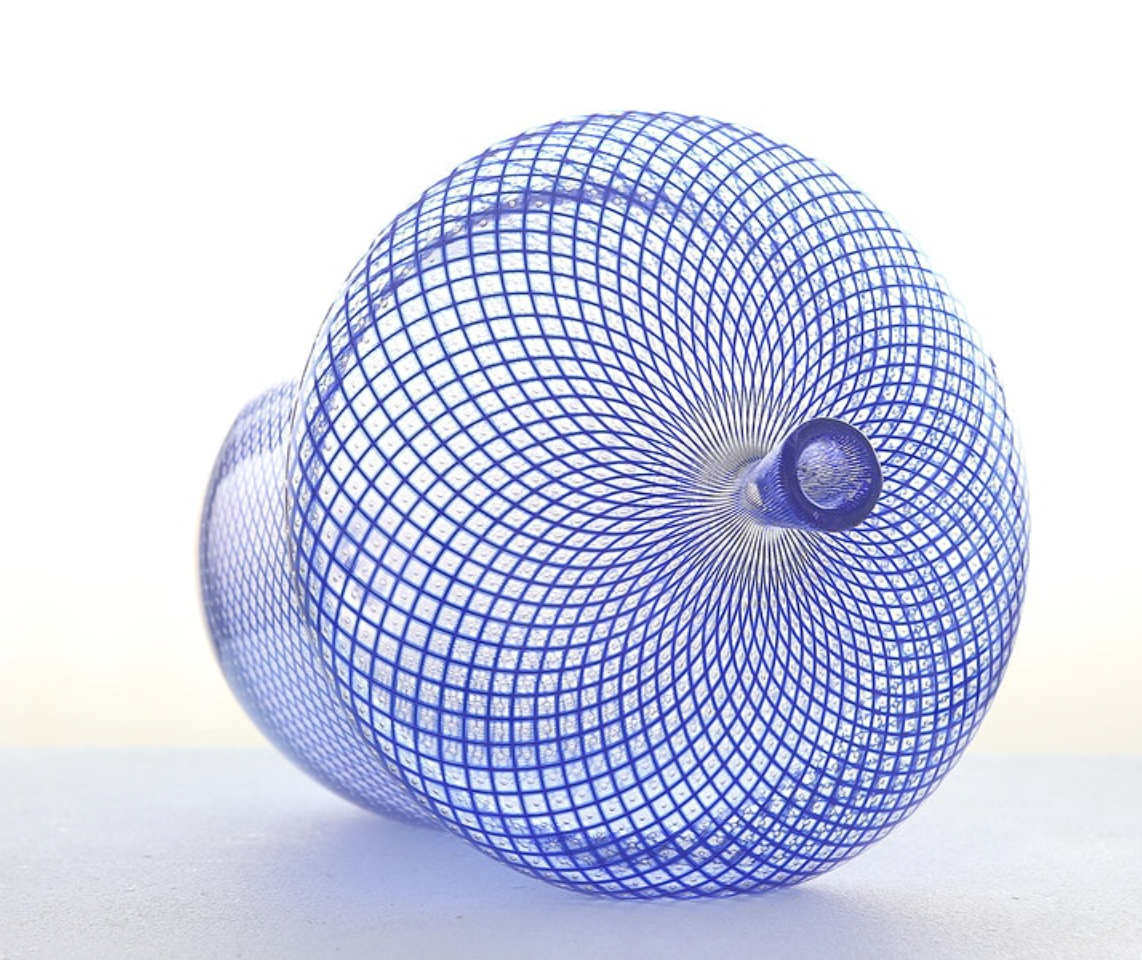

For Dante, this fire has never been put out. There is a continued desire to prefect, master, and develop as many techniques with glass as possible. This has led Dante to push for new forms and designs in their oeuvre. One of these designs embodies this fire within: the acorn. Dante was infatuated with acorns, something that could fall from the tree without being damaged and subsequently grow into something steadfast and strong. In a similar way Dante has grown in confidence and ability to create a huge variety of works. Notably Dante’s acorns are executed in reticello, one of the most complex forms of Venetian glass. Reticello requires a glassblower to create two forms of identical shape based around cylindrical canes of glass, these canes are then fused together in opposing directions to create a lattice effect, betwixt each lattice a delicate air bubble should appear to create a visual dot matrix pattern. Through the use of this technique Dante’s acorns proclaim themselves not to be naïve youths with potential for greatness, but rather prodigies of brilliance with advanced knowledge and abilities. Dante works as a single-handed artist, eschewing large teams, and places their own hand, breath, and iconography at the centre of each piece.

BEAUTY:

The beauty of Dante’s glass lies in the manner it transcends time. When Dante was first exposed to glass and its potential in the 70s, the mode was for artful blobs; these freeform shapes held little allure for Dante. It was witnessing the skill of Moore, who was able to produce a symmetrical on-centre vessels, that led Dante to explore more formalised shapes. Dante’s inspiration reaches back to classicism, with the formation of long necked vessels and structured bodies. When Dante, at the age of 23, unveiled the ‘Whopper’ series a shift in glass design sensibilities occurred. This series of enlarged and boldly coloured vases recalled the development of classical appreciation that occurred during the Renaissance. Reminiscent of vessel forms found in Parmigianino’s seminal work ‘Madonna of the Long Neck’, Dante’s classical forms have an iconographic history of elegance, refinement, humanist ideals, and a connection with our shared human existence. Dante’s elegant forms in their exaggerated scale create an emulation of the human body and allow the vessels to take on a personality of their own- something that the viewer can engage with.

Large glass forms offer new and intriguing challenges to the creator, glass can only be formed in relation to the size of the kiln available. This challenge presented by the physical constrains of manufacture allow Dante’s monumental glass vases to sit at the height of glass technicality. These vases join the realm of other monumental glass greats such as Dale Chihuly, an American glass blower whose work has been exhibited at Kew Gardens (2019) and the Victoria & Albert Museum (2001). These large works of Chihuly are more free form than Dante’s, but only serve to demonstrate the strict structural beauty that Dante creates through focusing closely on proportionality and line. Chihuly, through working with a team in a more hands-off conceptual approach, has created dynamic works that visually provoke and questions the expectations of form in glass. For Dante, the body and form are similarly integral to the aesthetic impact; with each work provoking through design but also pushing the boundary of physicality and the scale that a single glass artisan can produce rather than a team. Both artists clearly overlap in their appreciation of colour and technique and clearly display an aptitude for creating lavish colour stories that electrify their setting.

THE ETERNAL:

Carlo Scarpa, the notable 20th century architect, is one of the most significant names in the modern history of glassblowing. Working in many Venetian glass works through the early part of the 1900s. Scarpa, not unlike Dante, pushed for a revolution in the capabilities of glass design. Scarpa married two iconic crafts of Venice, glass and mosaic, in one with their Roman Murrine series that was unveiled in 1936. This technique, of combining small squares of glass together before being blown into fantastic shapes, was one that Dante spent years perfecting; it is through this Mosaic series that Dante expresses their connection with a legacy of Murano, Venice, Roman, and earlier glass cultures.

Through the ‘Vessel Displays’ series, Dante also explores the concept of the Eternal by engaging in the universal human activity of collecting and display. This form of displayed collecting stretches back to the Renaissance and the rise of the Wunderkammer, or Cabinet of Curiosities. These Wunderkammer were designed to allow the owner or viewer a chance to explore and understand the physical universe both natural and synthetic. Collecting is an innate activity found in every culture, making it one of the few shared activities that has existed throughout the whole of human history. For these ‘Vessel Displays’ Dante plays with the concept of collecting and the history of Wunderkammer. Dante creates a variety of different forms that display the variability and flexibility of glassblowing, Dante’s own dynamic range, and unveils the extraordinary universe of glass: with some angular; some curvilinear; some contemporary in form, and some historic in shape. By creating spaces that catalogue and explore this concept in glass we see an exciting look into aesthetics, the universal, and human achievement. Wunderkammer displayed the true variety, versatility and history of the natural and synthetic world and glass, rather poetically, is itself the mastery of natural elements transformed into the synthetic, and when presented in this manner, with its diverse history in tow, glass is heightened to its most symbolically potent form.

The Eternal is something difficult to capture and express; yet Dante, with their understanding of the lineage of glass forms and techniques manages to marry this illustrious past with the experimental verve of the now. This walking this line of historicism and contemporaneity is not a simple accomplishment, rather it speaks to the artistic vision and capability of one of the greatest living glass artists.

We are excited to offer our visitors a glimpse into the universe of Dante Marioni at Messums Yorkshire in our upcoming exhibition.

Following an outstanding opening of Malene’s work in Cork St, Malene Hartmann Rasmusen’s exhibition ‘Fantasma’ has relocated itself to Istanbul to be part of ‘Beyond the vessel: Myth and Metamorphosis in Contemporary Ceramics’.

It is too often the case that provincial artists (responding to their own culture or the mythologies of their own community) have to enter main, often western, centers of the world in order to make their name. The koc foundation in Istanbul is upending this. This exhibition looks decidedly outward and pays particular attention of the mythologies of different communities while highlighting the unifying quality of the ancient medium of clay itself.

Malene has drawn inspiration from the cultural outpourings of Scandinavia and her own past. Her work itself is very much responding to a journey that she is on and we are delighted to play a part in the physical journey of these works from Denmark to London and to Istanbul.

Shortly prior to exhibiting in Messums London Malene completed a ceramics residency at the V&A which has informed the works on show.