“Heat cannot be separated from fire, or beauty from The Eternal”

-Dante Alighieri

Glass making is a dialogue between many elements and many people; it requires patience, creativity and teamwork. Dialogues open new avenues of potential exploration between those that enter them. There is a clear parallel between two Dantes who set themselves apart from their contemporaries through pursuing revolutionary paths in their respective creative fields. The first Dante is Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) who developed the dynamic possibilities of literature in the Italian Renaissance through works such as The New Life and Divine Comedy. The heir to Aligheri’s maverick spirit is the second Dante, Dante Marioni (born 1964), one of the leading figures in contemporary American glass, who combines the same elements that their Florentine namesake put to the page into their own art: heat, fire, beauty, and The Eternal to create works that move beyond the expected and attempt to define and represent our own era. Dante Marioni is realising some of the most progressive and technically perfect vessels of our time.

Dante Alighieri’s work Divine Comedy tells the story of Alighieri’s imagined long journey through an Inferno (hell) to Paradise (heaven). Dante Marioni goes on a similar journey in their practice, manipulating through their singular skill the transformation of a heated form of glass, that is removed from the bowels of raging inferno, into a clear and cool structure- the antithesis of what it was, representing the magnificence of paradise. Glassblowing is the act of combining seemingly impossible techniques to transform and manipulate molten liquid into its antithesis without direct touch: a cool solid formation. This process can be temperamental, but the final product will never reveal the strife, skill, and strength that went into its production.

HEAT:

Glass has been desired as a material for thousands of years, dating back to Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, with some early pieces being created from 3600 BCE. Under the dynamic system of trade established throughout the Roman Empire, glass spread across the globe, leading to glass objects ending up in many unexpected places, including in Han Dynasty (202 BCE- 220 CE) Chinese tombs. After the fall of the Roman Empire glass production devolved to independent productions revolving around local techniques. It wasn’t until the 14th century when the Venetians pioneered techniques to produce tough and transparent glass that a rightful heir to the glass empire emerged – Venetian glass, complete with engaging forms, textures, and colour, became a desired product internationally. The Venetian way of life was inextricably linked to glass, with it being central to the economy, to such an extent that if a glassblower left Venice without permission thier family would be imprisoned until their return, and an assassin would be dispatched to stop the spread of glass related secrets if a glassblower failed to return. Despite being removed to the island of Murano (by a 1291 decree to prevent fires across Venice), glassblowers held a prestigious position in society that enabled special privileges, such as being able to marry into nobility, carrying extra swords, and the acquisition of wealth. It is from this dynamic legacy that contemporary glassblowing hails; just as the Dante Aligheri’s Inferno was filled with intrigue and drama, so too was the glass producing world.

Seattle, where Dante is based, is the centre of glassblowing in America. This area is infused with the same passion for glass that has been found in Murano for almost 1000 years. It was the vision of a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor, Harvey Littleton, to bring glassblowing out of the factories and into the studio and form a hub of artisans that would experiment and push glass to new heights. In 1962 Littleton created the first collegiate glass course in America and prompted a new wave of glass societies and locations for artisanal glass to develop. One of these was the Pilchuck Glass school, founded in 1971 by Dale Chihuly, was created as a space to encourage experimentalising in glass and yet was firmly based on mastering complex Muranese skills such as caning as Chihuly had trained in Venice. The methodology of teaching was based around artists teaching artists, which enabled a synthesis of techniques and ideas to develop out of this centre, this in turn solidified Seattle’s throne as the glass producing capital.

FIRE:

Dante Marioni has been at the forefront of artistic glass since the age of nineteen, pushing for new forms, colours, techniques, and inspiration. The fire to work with glass came from Dante’s father, Paul Marioni. Paul, a fellow glassblower, began working with glass in about 1972; for Dante when these early works of glass art were brought home it was a revelation. To be viewing glass not just as a something that could be handmade but even devoid of practicality was something refreshing and inspiring. This led Dante to work at a local glass blowing factory in Seattle as a teenager, and eventually training under the Muranese master Lino Tagliapietra and Americans Benjamin Moore and Richard Marquis. This transcontinental training places Dante firmly in the centre of contemporary glass, as well as continuing the legacy of Venetian Muranese glass. Dante’s ability was further cemented at the Pilchuck Glass School in Washington, where Paul Marioni also taught.

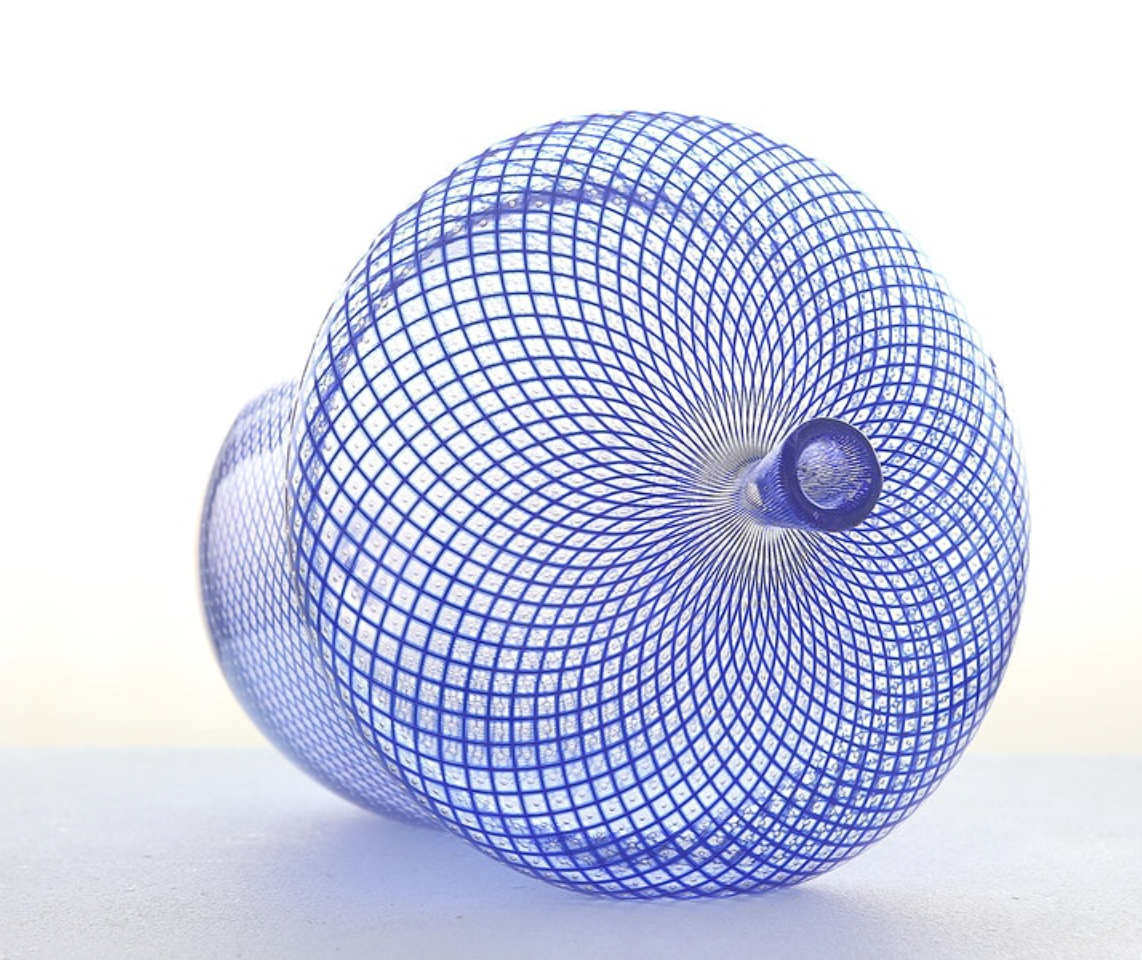

For Dante, this fire has never been put out. There is a continued desire to prefect, master, and develop as many techniques with glass as possible. This has led Dante to push for new forms and designs in their oeuvre. One of these designs embodies this fire within: the acorn. Dante was infatuated with acorns, something that could fall from the tree without being damaged and subsequently grow into something steadfast and strong. In a similar way Dante has grown in confidence and ability to create a huge variety of works. Notably Dante’s acorns are executed in reticello, one of the most complex forms of Venetian glass. Reticello requires a glassblower to create two forms of identical shape based around cylindrical canes of glass, these canes are then fused together in opposing directions to create a lattice effect, betwixt each lattice a delicate air bubble should appear to create a visual dot matrix pattern. Through the use of this technique Dante’s acorns proclaim themselves not to be naïve youths with potential for greatness, but rather prodigies of brilliance with advanced knowledge and abilities. Dante works as a single-handed artist, eschewing large teams, and places their own hand, breath, and iconography at the centre of each piece.

BEAUTY:

The beauty of Dante’s glass lies in the manner it transcends time. When Dante was first exposed to glass and its potential in the 70s, the mode was for artful blobs; these freeform shapes held little allure for Dante. It was witnessing the skill of Moore, who was able to produce a symmetrical on-centre vessels, that led Dante to explore more formalised shapes. Dante’s inspiration reaches back to classicism, with the formation of long necked vessels and structured bodies. When Dante, at the age of 23, unveiled the ‘Whopper’ series a shift in glass design sensibilities occurred. This series of enlarged and boldly coloured vases recalled the development of classical appreciation that occurred during the Renaissance. Reminiscent of vessel forms found in Parmigianino’s seminal work ‘Madonna of the Long Neck’, Dante’s classical forms have an iconographic history of elegance, refinement, humanist ideals, and a connection with our shared human existence. Dante’s elegant forms in their exaggerated scale create an emulation of the human body and allow the vessels to take on a personality of their own- something that the viewer can engage with.

Large glass forms offer new and intriguing challenges to the creator, glass can only be formed in relation to the size of the kiln available. This challenge presented by the physical constrains of manufacture allow Dante’s monumental glass vases to sit at the height of glass technicality. These vases join the realm of other monumental glass greats such as Dale Chihuly, an American glass blower whose work has been exhibited at Kew Gardens (2019) and the Victoria & Albert Museum (2001). These large works of Chihuly are more free form than Dante’s, but only serve to demonstrate the strict structural beauty that Dante creates through focusing closely on proportionality and line. Chihuly, through working with a team in a more hands-off conceptual approach, has created dynamic works that visually provoke and questions the expectations of form in glass. For Dante, the body and form are similarly integral to the aesthetic impact; with each work provoking through design but also pushing the boundary of physicality and the scale that a single glass artisan can produce rather than a team. Both artists clearly overlap in their appreciation of colour and technique and clearly display an aptitude for creating lavish colour stories that electrify their setting.

THE ETERNAL:

Carlo Scarpa, the notable 20th century architect, is one of the most significant names in the modern history of glassblowing. Working in many Venetian glass works through the early part of the 1900s. Scarpa, not unlike Dante, pushed for a revolution in the capabilities of glass design. Scarpa married two iconic crafts of Venice, glass and mosaic, in one with their Roman Murrine series that was unveiled in 1936. This technique, of combining small squares of glass together before being blown into fantastic shapes, was one that Dante spent years perfecting; it is through this Mosaic series that Dante expresses their connection with a legacy of Murano, Venice, Roman, and earlier glass cultures.

Through the ‘Vessel Displays’ series, Dante also explores the concept of the Eternal by engaging in the universal human activity of collecting and display. This form of displayed collecting stretches back to the Renaissance and the rise of the Wunderkammer, or Cabinet of Curiosities. These Wunderkammer were designed to allow the owner or viewer a chance to explore and understand the physical universe both natural and synthetic. Collecting is an innate activity found in every culture, making it one of the few shared activities that has existed throughout the whole of human history. For these ‘Vessel Displays’ Dante plays with the concept of collecting and the history of Wunderkammer. Dante creates a variety of different forms that display the variability and flexibility of glassblowing, Dante’s own dynamic range, and unveils the extraordinary universe of glass: with some angular; some curvilinear; some contemporary in form, and some historic in shape. By creating spaces that catalogue and explore this concept in glass we see an exciting look into aesthetics, the universal, and human achievement. Wunderkammer displayed the true variety, versatility and history of the natural and synthetic world and glass, rather poetically, is itself the mastery of natural elements transformed into the synthetic, and when presented in this manner, with its diverse history in tow, glass is heightened to its most symbolically potent form.

The Eternal is something difficult to capture and express; yet Dante, with their understanding of the lineage of glass forms and techniques manages to marry this illustrious past with the experimental verve of the now. This walking this line of historicism and contemporaneity is not a simple accomplishment, rather it speaks to the artistic vision and capability of one of the greatest living glass artists.

We are excited to offer our visitors a glimpse into the universe of Dante Marioni at Messums Yorkshire in our upcoming exhibition.

Our represented artist Charles Poulsen is featured in The Times newspaper this month. The image was chosen as one of the publications photographs of September 2020 and taken by James Glossop. The sculpture is Poulsen’s Skyboat an 11-metre wooden former fishing boat built in Whitby, which is now suspended on a wooden frame more than four metres in the air. The sculpture is created at Marchmont House in the Scottish borders and will eventually be supported by the oaks planted beneath it which will form a living cradle. The boat will appear to float and take up to 70 years to complete.

An exhibition of Charles’ 5ft square drawings will be shown at Messums Yorkshire from 31 October…read more

Performance Associate Anthony Matsena talks to Messums Wiltshire about Co-directing, choreographing and performing in lock down alongside his brother Kel and his plans for creating a film and live performance coming to Messums Wiltshire this September.

It has been an incredible year for Anthony Matsena. Following his sell-out performances here at the barn gallery, Anthony has been busy working on projects for the National Dance Company Wales and a brand new piece commissioned by Messums Wiltshire in response to the Elisabeth Frink studio – in situ at the gallery from Saturday 4 July. As with all our events at this time, the dance will now be performed online but Anthony will be here to introduce it to us ahead of time via Zoom.

Live Performance: Saturday 5 September – SOLD OUT

Online Screening: Saturday 5 September – Tickets Launched

channelling three distinct camera angles the performance

will be live streamed to an online audience

Full price – £16.50

Members price – £6.50

Discount for members using access code

A ground breaking synthesis of performance and art in the recreated studio of Elisabeth Frink. Set within the largest thatched building in the country, this one off performance production is created in response to these challenging and creatively vital times. A synthesis of the legacy and output of Frink, the repercussions of COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement forms the basis of this pioneering contemporary dance performance.

Matsena Performance Theatre is Anthony and Kel Matsena – Zimbabwean born and Welsh raised brothers. Through their experience of being brought up in an Afrocentric house and having Eurocentric schooling, they have built a love and curiosity for telling stories that express themes of culture, race, change and belonging. These two incredibly talented young brothers are adding their voices to a movement that included mass uprising, civil unrest and cries to stay connected and not numb to the world around them.

Referring to both the global pandemic and the numerous cases of injustice and conflict around the world Anthony says, ‘there has been a whole lot of loss and an insurmountable amount of fear that’s crept up in people’s lives and it’s become normal which is frightening… that I see people’s lives being lost as numbers or statistics.. that worries me.’ The Title behind the live and online performance is the unsettling question ‘are you numb yet?’ Kel astutely discusses this discomforting phenomenon of instant global news, where information overload means that although ‘the news of last week is extreme […] it’s still last week’s news’. Very few artists and performers are successfully dealing with these unsettling notions and the sudden awareness of how race has been a blinding problem for so many.

In many ways the natural medium with which to have these conversations is through the arts and very particularly live performance. Anthony points out that there is a parallel between life and live performance that does not occur in other art forms. ‘I like the high stakes of theatre.. if the magic of coping with what goes wrong is relevant to our lives then time is linear. Life is about coping with whatever happens, sometimes in theatre something falls.. a light goes.. someone feints. you deal with it and still perform.. and that part of it.. that’s the magic for me.’

The realisation is so recent in our history that we are still grappling with the language with which to discuss it. Kel and Anthony are not here to raise their voices, the performance is powerful embodiment of a language that does far more and asks the question about being alive to others concerns.

The title “ Geometry of Fear” was conceived by Art critic Herbert Read and refers to a phase of British figurative sculpture expressing post-war anxieties. Dame Elisabeth Frink, a child of her time and much affected by growing up during the war embodied these sculptors’ work and aspirations. These visceral and tortured looking sculptures caught Frinks wider interest in the Human condition and the language of sculpture that Frink inhabited. Frink’s goggle heads are perhaps most representative of her work and preoccupation with the inhumanity inherent in the blank and unapproachable archetype of power personified by the male figure. The goggles are polished, reflecting back any scrutiny, any chance at a mutual exchange. They could be seen as a political or institutional body, and are every cruel act anonymously hidden behind the term ‘they’ where power is so often abused. In the words of Elisabeth Frink, ‘we no longer respond properly to atrocities, if I had a religion it is that every man should be free in his spirit’. With the performance happening in and around the actual building that Frink created her sculptures, the parallels across time and artist cannot be ignored. As Anthony says, ‘fairness and equality should be the standard and it’s never been’. Put simply by Kel, ‘if we believe in equality, we have to fight for it.’

‘Finally, people are having conversations that should have been had centuries ago but there is uncertainty about how we deal with those conversations.’

Kel Matsena

‘We cant do a lot but we can use what we have and that’s our art, to try and affect change.’

Anthony Matsena

An exhibition of new paintings by Kurt Jackson opened last week with great excitement. ‘My Father’s River’ traces Kurt’s journey along the River Stour in East Anglia.

The day began with a packed curator’s tour of ‘My Father’s River’ led by Johnny Messum, before moving to the Royal Academy Lecture Theatre where Kurt spoke to over 300 people about his work both as an artist and an environmentalist. He talked through the major projects that have come to define his practice as an environmentally informed artist.

His residency aboard the Greenpeace ship Esperanza was described in vivid detail alongside excerpts from a BBC documentary.A clip of Greenpeace activists attempting to document damaging fishing practices on a small rib in rough seas while Kurt is continually drawing, documenting the action around him encapsulates his determination and versatility as a painter.

This versatility was also apparent in Kurt’s long stint as artist-in-residence at Glastonbury Festival. The rapid brushstrokes that usually describe the natural landscape were now applied to vast crowds and wild performances. Kurt is clearly a polymath; from designing trophies for environmental awards, working in bronze, pewter and a more recent foray into glass, his enthusiasm for making was increasingly evident.

For most of the talk however Kurt discussed the landscape painting for which he is most well known. That Kurt’s paintings so energetically and vividly evoke these landscapes is less surprising after seeing footage of him painting outside in the elements, canvas spread out on the beach. He gave real insight to the excitement and love of nature behind his works – from protected and fragile environments of rich biodiversity to patches of grass by service stations.

After the talk, a crowd headed towards Messums London for mulled cider and mince pies surrounded by Kurt’s magnificent paintings. Beginning at the river’s source on Wratting Common in Cambridgeshire, the paintings document the river as it winds through the East Anglian countryside, along the border of Suffolk and Essex to where it meets the North Sea at Harwich.

Kurt often painted the Stour with his father who lived by the river for three decades, swimming in it every day. In this body of work, Kurt has rediscovered the river that was so important to his father as well as capturing a fragile and varied landscape with the eye of a keen environmentalist.

‘Source to Sea’, or ‘My Father’s River’, is on show at Messums London until 21st December, followed by exhibition of new works following the Fonthill Brook and River Nadder at Messums Wiltshire. ‘Fonthill Brook’ opens in the Long Gallery at Messums Wiltshire 10 January – 16 February 2020.

ARTIST’S TALK: 27 & 28 November 2019

Albert Paley’s talk and slide show at Messums London traced the 50 years that he has been working in metal; from making intricate pieces of gold and silver jewellery measured in centimetres to sculptures the size of houses, 30 feet high.

At the root of all his designs are his drawings in pencil he said, that fill the drawers and sketchbooks of his 50,000 square foot studio in Rochester, New York. ‘Drawing is fundamental – it gives you a vocabulary so you can understand what you see,’ he said, adding that his jewellery expressed ‘an attention to detail, a refinement of line.’

Thinking through doing is how he works he says, and as his technical skill has grown so has the ambition of his sculptures. ‘Technique is a way to manage thought development; I don’t know what I’m doing until I start working,’ he explained.

Born in Philadelphia, Paley attended the Tyler School of Art where his earliest works were direct carvings in wood and stone in the tradition of Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth and he showed us a picture of a delicate, sensuous Rodin-esque sculpture of a woman he carved out of white marble.

Paley’s training was not only manual but academic with an education in the techniques of Renaissance masters like Cellini, Leonardo and Michelangelo as well as the Mannerist and Viennese Secessionist painters of which he is particularly fond.

Early in his career Paley had imagined he would be a goldsmith ‘for the rest of my life,’ but irked by the perception of jewellery as a ‘minor art, rather than what it truly is – a fine art,’ he started making bigger pieces starting with a set of enormous gates facing the White House.

Albert with Johnny Messum at Messums Wiltshire

‘Using metal is like drawing in space’ he said. ‘Punching, ribboning and blasting, the gates enriched my public exposure and allowed me to interface with architecture, pushing me into a new arena’ he said. Going through gates is an act of passage, he said, ‘they are ceremonial archways.’

Consistently throughout all his work appear flowing, sinuous, natural forms – in particular vegetation – within ordered, mathematical structures.

‘My design philosophy is organicity in that one line begets another whether it is in metal or any other material,’ he says.

In 1979, Paley was asked to make two gates for the antechamber of the New York Senate. The Albany gates, as they are known, reflected the nascent fear of terrorism in public spaces in their spiky, thorn-like design protecting the heart of government.

In his talk, Paley rattled through an astonishing array of gates and fences, benches and grills and freestanding ‘sentinels’ or sculptures that he had made, all created with an unerring sense for form and each bigger than the last. He describes his studio as his sanctuary adding that his 16 staff were like the members of an orchestra of which he is the composer.

Paley said he tried to use design to bring a sense of modernity into historic spaces and talked much about the play of light and shade in his work and the beauty of rustification.

The Fence of the Hunter Museum is one of Paley’s wildest works to date where the lines of metal seem to hover in space like banners or whips.

In his recent works, Paley has tended increasingly to paint metal and patinate it in a range of hues.

‘Colour solicits emotion’ he said. ‘Shadows are beautiful but ephemeral and colour adds into that.’

Pointing to a range of eight sculptures he made to adorn the staircase of the Wortham Center for the Performing Arts in Houston, he said the effect was to create ‘a whole sensuality of folded metal, play of light and tromp l’oeil.’

The talk ended with a description of how Paley created the gates for St Louis Zoo, and we saw a fine picture of him next to a metal rhinoceros he had made.

In a question and answer session after his talk somebody in the audience mentioned that the computer has led to the dematerialisation of form and that the importance of objects in the realm of fine art is in a state of flux.

‘Fundamentally, art deals with the human condition’ replied Paley, ‘whether it’s a personal response in canvas or in the public arena like the music of Wagner. Metal articulates emotion beautifully; there is an honesty and integrity to being a blacksmith. It’s all about sharing that language.’

Albert Paley’s talk was part of his exhibition ‘Drawings and Sculptures’ at Messums London which comprised of his architectural two-dimensional works and smaller scale sculptures and maquettes. An exhibition of Albert’s ‘Large Sculptures and Architectural Works’ including examples of his monumental gates, will be open at Messums Wiltshire 4 July – 30 August 2020.

Press coverage:

Financial Times – How to Spend It ‘Mind-blowing Metalwork at Messums London’

Artlyst ‘Three London Shows November 2019’

Laurence Edwards’s work has found its way into stately homes, public parks and domestic spaces. The versatility of environment that his work has thrived in showcases its ability to own the space around it, no matter how vast or small, domestic or wild. The difference between a thirteenth century tithe barn in Wiltshire and a Mayfair gallery might be boundless but the striking and enigmatic figures of Laurence Edwards populate both spaces with an atmosphere of mysterious omniscience.

The variability, however, between the individual pieces is exemplified by their curated groupings and placings. The collection of works in Wiltshire for example demand more from their space. Their volumous and shadowy stature possess their own kind of gravity while the pieces in London are preoccupied by more delicate forces; reflection, balance and line.

Wiltshire – Volume

Perhaps the first impression one might get from walking into the Barn and finding yourself amongst these towering characters is the effect of their scale. Not only scale in relation to the building or even to each other but to the viewer. One is confronted by the uneasy feeling of being looked down on from a height or the humbling experience of being eye to eye with a bust larger and taller than oneself. The lofty ceilinged space gives a sense of cathedral-esk verticality that lends a biblical tone to the weighty subjects.

London – Line

The preoccupations inherent in the pieces in Cork St are less to do with volume and more to do with tensions and forces such as that of rope, ties and supports. They elicit notions of the push and pull of encasement and a desire to break free, or the heaviness of the burden many of them carry. Often they suggest some conflict with visible outer forces and often invisible inner forces pertaining to the male psyche. Whatever their struggle these pieces are created with a lighter hand, they are the drawn line solidified in bronze.

Following an outstanding opening of Malene’s work in Cork St, Malene Hartmann Rasmusen’s exhibition ‘Fantasma’ has relocated itself to Istanbul to be part of ‘Beyond the vessel: Myth and Metamorphosis in Contemporary Ceramics’.

It is too often the case that provincial artists (responding to their own culture or the mythologies of their own community) have to enter main, often western, centers of the world in order to make their name. The koc foundation in Istanbul is upending this. This exhibition looks decidedly outward and pays particular attention of the mythologies of different communities while highlighting the unifying quality of the ancient medium of clay itself.

Malene has drawn inspiration from the cultural outpourings of Scandinavia and her own past. Her work itself is very much responding to a journey that she is on and we are delighted to play a part in the physical journey of these works from Denmark to London and to Istanbul.

Shortly prior to exhibiting in Messums London Malene completed a ceramics residency at the V&A which has informed the works on show.

We are delighted to announce that Messums will now represent the Australian artist Daniel Agdag in Europe and North America. Following his sell-out show at our sister gallery Messums Wiltshire, Daniel’s collection of intricate scalemodels can be viewed here in Cork Street until this Friday 12 July.

Daniel is an artist and filmmaker based in Melbourne, Australia, whose practise sits at the nexus of sculpture and motionography. He creates highly detailed sculptural pieces that have been described as architectural in form, whimsical and antiquated in nature and inconceivably intricate.

Daniel predominately works in cardboard. Drawn to its utilitarian origins and monochromatic presentation, he creates a paradox of fragility and strength with structures that resemble architectural forms and machines by utilising a medium that is essentially paper and preserving them under glass vitrines or bell jars.

Whilst his work is predominantly realised in cardboard he has made work in steel, wood and glass in recent years as part of translating his elaborate ideas into large scale public art sculptures, in 2014 he completed a large-scale public commission ‘The Inspector’ in Abbotsford, Melbourne.

The son of Armenian immigrants, Daniel Agdag studied Fine Art before his interest in moving image drew him to filmmaking. He received a Masters in Film and Television from the Victorian College of the Arts in 2007.

He has exhibited solo shows in Melbourne and New York and been presented at several international art fairs: Melbourne Art Fair; Sydney Contemporary; Art Central Hong Kong; VOLTA Basel; Art Fair Tokyo. His work is held in private collections in the United States, Japan, Hong Kong, Australia and Europe. He has completed several private commissions, notably for Hermès Paris.

To see our collection of Daniel’s artworks click here

Until Friday 28 June

For one week the team of curators from the Pod at Messums Wiltshire, our sister gallery in Tisbury, will host a pop-up exhibition in the windows of Messums London on Cork Street to showcase works by talented British and international makers.

The Pod at Messums Wiltshire is a unique retail space inside a 13th century tithe barn, the largest thatched building in the country. It presents a fusion of artists and makers brought together to explore the margin where art meets design and craft. Artist makers include those working in wood, ceramics, textiles and glass from a range of makers who are original in their execution of the creative process. Each item found has a story behind it; a story of the maker and their journey and a story of the end product. All handmade, all using materials in a way that demonstrates their true nature.

Each artisan understands the material they work with to create works to be valued and cherished in a way that is the antithesis of a throw away, quick fix society.

There are makers that are interested in sustainability in the textile industry, using offcuts and surplus fabrics in an ingenious way to produce finished pieces that are at once visually arresting and practical.

Whether it is ceramic or paper, each item is made by hand in small quantities by individuals or as part of a small studio so traceability is possible and connections are made by us with the makers create unique pieces that are often a response to our magnificent setting – a 13th century tithe barn that is one of the finest in the country.

They range in price according to the labour involved and scale of the finished works as we support local makers, as well as national and international artists and artisans.

For more information click here